If there ever was a time to consider a career shift into software engineering, it’s now. The demand for developers continues to rise as businesses rapidly digitize to stay competitive. If you choose to ride that crest, you’ll enter a field with immense growth potential and a wide range of career prospects.

With an average salary of $131,450 in 2024, the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics projects that demand for software developers, quality assurance analysts, and testers will grow about 17% between 2023 and 2033. This strong outlook reflects a job market increasingly defined by competition for technical talent. Notably, this rate of growth far outpaces the average for all occupations.

The search query “how to become a software engineer” has surged in popularity, not just among new grads, but increasingly among mid-career professionals in marketing, product, and operations roles. These individuals are picking up programming languages like Python, tinkering with automation scripts, and launching side projects. They’re not quitting to become full-time developers. They’re trying to close delivery gaps inside teams that are overstretched.

For engineering leaders, this isn’t a curiosity. It’s a signal. Professionals are trying to solve problems faster than IT or engineering can respond. That presents both an opportunity and a management challenge. It also raises important questions: Should you invest in upskilling these internal users? Can they truly become contributors to production systems? Or does this trend create more risk than value?

Why Your Colleagues May Transition to Software Engineering

The growing overlap between technical and non-technical roles is driving this trend. Business-side professionals often rely on software solutions, dashboards, and integrations to get their work done. But when those tools fall short, they start exploring ways to extend or customize them.

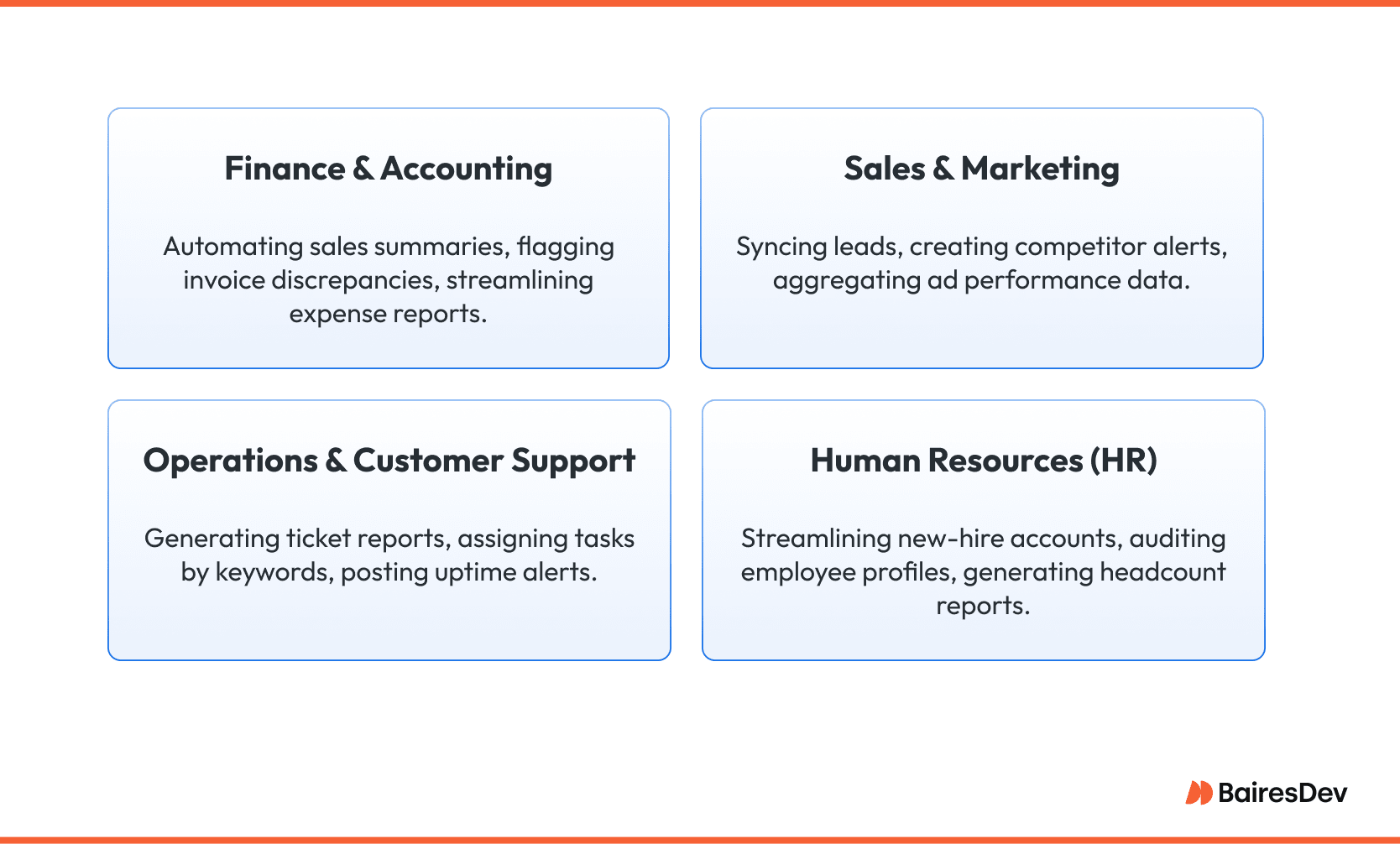

For instance:

- A marketing lead may need to analyze campaign performance using real-time data that the BI team can’t prioritize.

- A product manager might want to validate user flows by building interactive prototypes.

- An operations director could look to automate repetitive reporting tasks to save time.

In all these cases, learning to code isn’t a hobby, it’s a way to reduce friction. When timelines stretch and backlogs grow, some professionals take the initiative to bypass engineering queues by building their own lightweight solutions. They’re not aiming to become a developer in the traditional sense but to apply software engineering and problem solving skills to their functional work.

The Upside: Initiative, Business Fluency, and Embedded Context

Mid-career professionals bring advantages that junior developers often lack. They understand the business deeply, know the customer workflows, and have context around internal pain points. These qualities make them uniquely suited to build tools that solve real problems, even if their technical skills are still developing.

Some benefits of this trend:

- Faster turnaround on small internal tasks

- Greater cross-functional autonomy

- Stronger communication between technical and non-technical teams

- Early validation of ideas before committing engineering time

When non-engineers apply their domain knowledge to internal software projects, they often surface valuable edge cases and usability insights that engineers alone might overlook. Many software developers work alongside colleagues who now bring basic software development skills to the table. This can ease collaboration, particularly when the non-engineer understands concepts like version control systems, continuous integration, and how to use integrated development environments.

The Risks: Fragile Solutions and Shadow Tech Debt

But these benefits come with risks. Self-taught developers, even if motivated, often lack the discipline and experience to write production-quality code. Their tools may work in isolation but fail to scale or comply with internal standards.

Common issues include:

- Hardcoded credentials or insecure data handling

- Lack of test coverage or version control

- Poor documentation and maintainability

- Unclear ownership of critical scripts or tools

- Non-compliance with data governance or regulatory frameworks

Some attempt mobile development or dabble in web development, but without understanding software engineering principles or the full software development life cycle, these efforts can introduce long-term risk. Often, they’re unaware of the demands enterprise environments place on maintainability, scalability, and security.

What Engineering Leaders Should Do

This trend can’t be ignored, but it shouldn’t be overestimated either. Engineering leaders should approach it with clear-eyed pragmatism. These self-taught contributors are valuable, but they are not a substitute for experienced engineers.

Recommendations:

- Recognize and support high-potential talent. If someone on the business side shows aptitude and drive, consider offering structured learning paths or mentorship from your team.

- Set clear boundaries. Define what types of scripts or tools can be developed outside engineering, and under what conditions.

- Implement lightweight code review. Have a process where technical staff can review internal contributions before they become operational dependencies.

- Gate access to sensitive systems. Ensure authentication, data handling, and deployment practices meet security standards.

- Track internal tooling formally. Create visibility into what tools exist, who owns them, and whether they touch customer or business-critical systems.

Encouraging them to build projects or contribute to open-source projects is helpful, particularly when paired with coaching on engineering principles and critical thinking. Otherwise, even a highly competent developer in training can unintentionally cause issues.

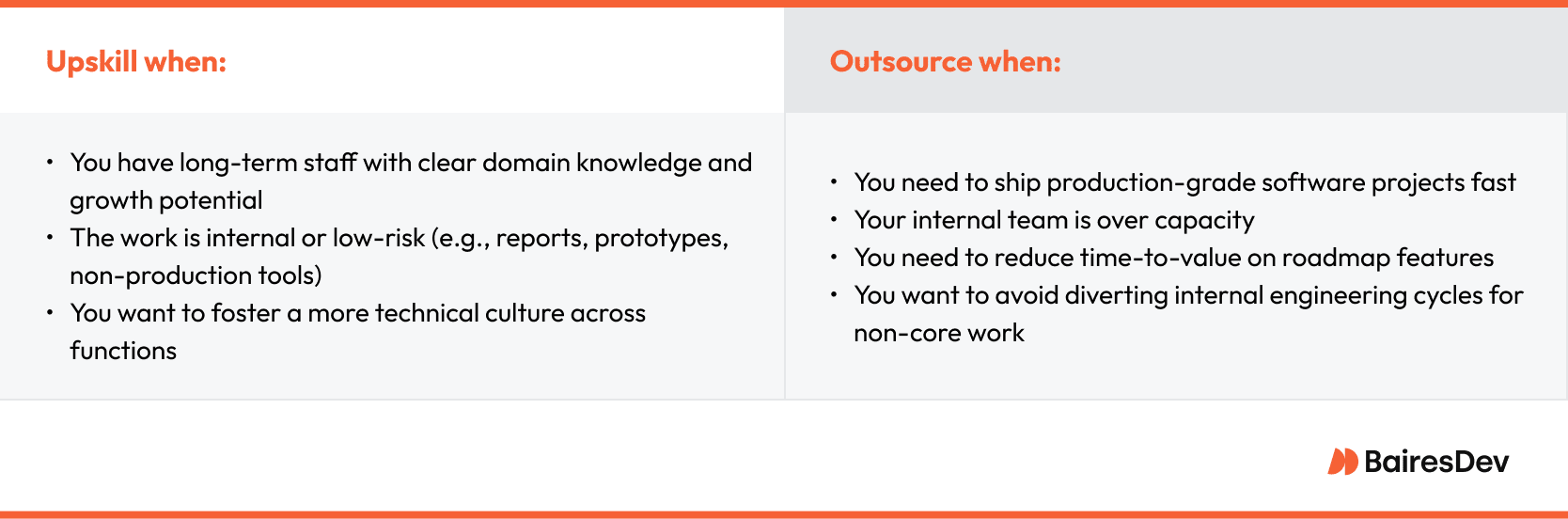

Upskill or Outsource? Know When to Do Each

Upskilling internal staff can be a smart long-term investment, especially for technical PMs, analysts, or other hybrid roles. But it’s not the answer when velocity, scalability, or quality are non-negotiable.

The reality is that most enterprise teams need both. Use outsourcing to protect and scale delivery capacity while letting internal upskillers grow into more technical roles at a sustainable pace. Freelance projects might help aspiring software engineers gain hands-on experience, but full-time, scalable development still demands dedicated software teams.

What This Trend Says About Your Team

If non-engineers are reaching for code, it may be a sign that engineering support isn’t keeping up with demand. This isn’t always a failure. It may simply reflect a team that’s being asked to do too much with too little.

Signs you might need to rebalance:

- Business teams create workarounds or tools without engineering input

- Requests for internal support go unaddressed for weeks or months

- Workflows rely on unsanctioned automation or scripts

- Teams are trying to solve recurring problems outside your SDLC

This is also a reflection of the software industry’s increasing demands on soft skills, critical thinking, and the ability to solve problems beyond just writing code.

From Coding Challenges to Critical Thinking: Where This Trend Leads

In the long term, a technically fluent business team is a net positive. When PMs, marketers, or analysts can speak the language of code, collaboration gets easier. Specs are clearer. Handoff is smoother. And ideation happens faster.

But this requires guardrails. Engineers should set standards. Leaders should support learning without sacrificing velocity. And companies should invest in both internal growth and external capacity as needed.

Support your colleagues’ efforts to explore programming languages relevant to your stack through real-world projects that strengthen technical expertise and team readiness. Encourage them to take online courses, practice coding challenges, and even mock technical interviews that mirror what candidates face in real software engineering jobs. Understanding core concepts like data structures, operating systems, and object oriented programming can help them build better software applications and maintain software systems more effectively.

Final Thoughts

The rise of self-taught coders across your organization is worth paying attention to—not because it solves your delivery gap, but because it reveals it.

These professionals aren’t trying to replace web developers or join your Android development team. They’re trying to get work done. The more you understand their motivations and limitations, the better positioned you are to scale the right way, with a mix of upskilling, structure, and outside help.

They may not hold a computer science degree or come from a bachelor’s degree program in information technology, but they often bring a mindset of continuous learning and a desire to write software that solves real business problems.

FAQs

Should I encourage non-engineers on my team to learn to code?

Yes, with boundaries. Encourage technical literacy and offer learning resources, but make sure they’re not taking on work that requires production-level quality without engineering involvement.

Can these self-taught contributors be integrated into the engineering team?

In some cases, yes. If someone shows aptitude, drive, and a sustained interest, they may transition into a hybrid or entry level software engineer role. But this takes time and structured mentorship.

What kind of work is safe for non-engineers to automate or build?

For a professional who has also studied software development can build internal dashboards, one-off data reports, or prototypes are usually safe starting points. Anything touching customer data, authentication, or production infrastructure should go through engineering.

How do I prevent shadow tech debt from these efforts?

To avoid shadow tech debt, introduce a lightweight intake or review process. Track internal tools in a shared inventory. Have engineers do spot reviews or offer guidance sessions to prevent poor practices from spreading.

How do I balance upskilling with outsourcing?

Use upskilling for long-term talent development. Use outsourcing for urgent, high-quality delivery. These aren’t mutually exclusive—they work best together.

Should I formalize internal tools built by non-engineers?

If they’re widely adopted or critical to business functions, yes. Assign ownership, ensure code quality, and bring internal tools built by non-developers under engineering or IT oversight.

What risks should I watch for?

In highly regulated domains or applications involving embedded systems, even minor oversights can introduce major compliance or reliability issues. Keep an eye out for data security, compliance violations, unscalable code, undocumented tools, and unclear ownership are the biggest risks. Treat any self-built tool as a potential production dependency.

How do I talk to leadership about this trend?

When addressing leadership, frame it as a sign of demand outpacing delivery. Use it to advocate for either more internal headcount, selective outsourcing, or investment in enablement tooling.

Is this trend a threat to engineering?

If managed well, this trend can complement engineering. But without boundaries, “citizen developers” can create long-term drag.

What support systems should I have in place?

For support options, offer office hours, documentation templates, coding standards, and mentorship. Encourage staff to build their own projects or explore specific technologies relevant to their function. These low-cost structures can go a long way toward reducing risk and amplifying value.