You’ve managed engineering teams. You’ve inherited orgs. But building a new product team from scratch? That’s different, and most of the advice out there won’t help you.

The 101 guides skip the hard parts. Who should you actually hire first? How do you avoid creating the silos that’ll strangle you in six months? When should you bring in external help, and how do you keep them from becoming a liability? This article tackles those questions.

Three things matter most: getting the right people, knowing when to scale with outside help, and setting up a team structure that won’t collapse.

Let’s start with hiring.

How to Actually Hire Product People

Building a new product team means you get one chance to set the DNA. Unfortunately, many companies blow it. Their hiring process is slow, political, and optimized for the wrong things. Every person you bring on sets expectations for what matters here, so this isn’t just about filling seats.

Here is the truth nobody wants to hear: you’re not losing good candidates to better offers. You’re losing them because your hiring process screams “we’re disorganized.” Four weeks, five rounds, three different interviewers asking the same questions. That’s not thoroughness. That’s a big red flag for in-demand talent.

To build a high-performance cross-functional team, you need to fix three things: who you look for, where you find them, and the speed of your decisions. My experience has taught me that speed matters more than people think.

Trajectory Over History

Don’t hire resumes. A common mistake is hunting for the perfect background and overvaluing domain expertise.

“Must have 5 years in FinTech.”

You can teach someone your domain. You can’t teach them how to think, or whether they’ll push back when your idea is bad.

I hire for trajectory. I want the person who is bored at their current job because they’ve outgrown the problems there.

The whole “empowered pod” model fails if you staff it with order-takers, people who just execute. You need problem-solving, not people who check boxes.

Hiring a Product Manager Who Can Say No

You’re looking for “product sense,” that instinct for what matters to users and for what moves business goals. The problem is, you can’t find it by asking trivia questions. Stop the theoretical stuff. Run a case and test their ability to handle resource allocation under pressure.

The Test: “We have two weeks left in the quarter. Engineering says we can’t ship both the Mobile update and the Enterprise reporting feature. Which one do you kill, and how do you explain it to the CEO?”

- Weak Answer: “I’d ask the engineers to work overtime,” or “I’d try to do a lite version of both.” (This is a project manager, not a product manager.)

- Strong Answer: “What’s the goal for the quarter? If it’s retention, we ship Mobile. If it’s revenue, we ship Enterprise. I’d cut the other one, explain the data to the CTO, and take the heat.”

That demonstrates product strategy, and that’s what a strong product hire needs.

| Evaluation Criteria | The “Project Manager” (Weak Hire) | The “Product Leader” (Strong Hire) |

| Focus | Backlog execution and hitting deadlines. | Business outcomes (ROI, retention) and strategic impact. |

| Problem Solving | Defaults to immediate solutions (“Let’s build X”). | Investigates data and root causes before proposing direction. |

| Conflict Style | Avoids conflict to keep stakeholders satisfied. | Makes hard trade-offs and defends decisions with data. |

| Success Metric | Output (features shipped, tickets closed). | Outcome (revenue lift, customer behavior change). |

Hiring “Product-Minded” Engineers

This is a role many leaders overlook. You don’t want a software development team that waits for a perfectly-specced ticket. You want partners who’ll challenge the PM and product designer when something doesn’t make sense. Someone who challenges product priorities and your assumptions.

Test for this with a user problem, not a LeetCode puzzle.

The test: “A user says they can’t find the ‘export’ button.”

- Weak Answer: “Okay, where should I move it?”

- Strong Answer: “Why do they need to export? Are they trying to manipulate the data in Excel because our reporting tool isn’t working properly? If we fix the report, maybe we don’t need the button at all.”

The best engineers understand that code is a liability. They try to solve problems without writing it first.

They may say something like: “Building this properly takes four weeks. I can get you a 90% solution in three days that solves the immediate problem. Which matters more?”

That’s business judgment on display. That’s what you need in a product specialist.

| Evaluation Criteria | The “Code Monkey” (Weak Hire) | The “Product Engineer” (Strong Hire) |

| Work Style | Waits for fully spec’d tickets. | Challenges requirements if they don’t solve the user problem. |

| Estimation | Estimates based on code size or complexity. | Estimates based on business value and time-to-market. |

| Output View | Treats “writing code” as the core job. | Treats “solving the problem” as the core job—even if no code is needed. |

| Collaboration | “Just tell me what to build.” | “Why are we building this? Is there a faster path?” |

Hiring a Designer Who Thinks in Systems

Skip the “pretty layouts” designer. You need a product designer, someone who thinks in systems and understands how user experience drives business outcomes. Their job isn’t just making things look nice. It’s shaping the customer journey, removing friction, and influencing key metrics like activation, retention, and conversion, all while keeping the product coherent as it scales.

The Test: Ask them to walk through their portfolio, then interrupt. “This looks great. Tell me about three ideas you killed for this project and why.”

You’re testing for judgment, not taste. Strong designers can explain how research insights turned into product decisions, how trade-offs were made, and what measurable impact their work had. If they’re talking more about user behavior, mental models, and system constraints than fonts and colors, you’re on the right track.

| Evaluation Criteria | The “Artist” (Weak Hire) | The “Systems Thinker” (Strong Hire) |

| Portfolio | Prioritizes visuals, trends, and aesthetics. | Prioritizes workflows, IA, and system-level coherence. |

| Process | Shows only polished final assets. | Shows prototypes, failed approaches, and iteration paths. |

| Feedback | Gets defensive and treats critique as personal. | Seeks critique as input to accelerate iteration. |

| Tools | Fixated on Figma techniques and pixels. | Fixated on user psychology and interaction patterns. |

Speed As a Competitive Advantage

Good candidates move fast. Not all of them are off the market in 10 days, but enough of them are that your “thorough” process becomes a filter for people with no other options.

You need to match the market’s pace, not your calendar’s pace. If your process takes four weeks, you are inadvertently building an adverse selection mechanism: you filter out the high-performers who got snatched up by faster companies, and you are left with the candidates who have no other options.

You have to treat hiring like a business operation. Your target is “Hire-to-Offer” in 14 days.

Get Aligned Before You Post

Misalignment kills more hiring timelines than anything else. Every stakeholder needs to sign off on the job description, salary band, and interview panel before you post the role. No “iterating on the role” while candidates sit in limbo. If you are internally discussing the role and salaries as candidates wait in the pipeline, you’ve already lost.

Three-Round Cap

Three rounds is enough. Ditch the marathon. You do not need seven people to agree on a hire. You need a clear signal. A streamlined process consists of three specific steps: a recruiter screen for trajectory, a technical case study to verify execution, and a final leadership call for culture fit. Schedule these back-to-back if possible.

Pre-Approve the Budget

The final bottleneck is usually the offer approval. You should pre-approve the budget before the finalist interview even happens. When you find the right person, you must be able to make the verbal offer on the spot and send the contract immediately. Speed signals competence. The best candidates are usually fleeing bureaucracy, and you don’t want to become what they are running from.

Don’t view speed as something that is lowering your standards. It’s about signaling that you’re decisive and respect people’s time.

When to Scale with External Teams

You can’t hire fast enough. Nobody can. At some point, you’ll need external help: freelancers, agencies, nearshore teams, etc. This is where leaders make expensive mistakes: they try to outsource the strategy, not just the execution.

Here’s the golden rule: never outsource product decisions.

You can scale your development team with contractors, but the “what” and the “why” must live in-house. Your Product Manager needs to be breathing your air, talking to your customers, and living in the business context. If you hire an agency to “do product management,” you aren’t getting an actual Product Manager. You are getting a Project Manager who focuses on timelines, not product success. They cannot make the hard trade-offs that matter when the pressure is on.

Granted, there are exceptions for mature products with rock-solid documentation, but assume you need in-house product ownership. Exceptions aside, product management needs to live in-house.

Nearshoring vs. Offshoring (It’s Not Just Semantics)

Don’t confuse these two. They’re completely different plays.

Offshoring is a Cost Play

Offshoring to a region with a 12-hour time difference is purely a cost-saving move. It is also an Agile-killer.

When you have zero overlap, “real-time collaboration” becomes impossible. Your stand-ups turn into emails, and your team turns into a ticket queue. A simple clarification on a requirement takes 24 hours to resolve because the development teams are passing ships in the night.

Nearshoring is a Velocity Play

Nearshoring to a place with 4-6 hours of overlap? That’s a velocity move. You optimize for overlap hours, not the lowest hourly rate.

That overlap is the difference between a vendor and a partner. It allows external engineers to sit in your stand-ups, challenge your designers, and collaborate closely when production breaks. They feel like an extension of your internal team and should be treated as such.

The First 30 Days

Success or failure with a nearshore team is decided in the first month. Don’t just toss them a backlog and hope it works out. You need a real integration plan. Target: cut PR cycle time by 30% within 30 days.

- Assign a Buddy: Pick one of your solid senior engineers to be their guide. Not their manager—their guide. Someone who answers the dumb questions: how to navigate the repo, who owns which API, why the build keeps failing. This one connection prevents them from feeling stranded.

- Give Them Real Access: They go in your main Slack channels, not some separate “nearshore team” channel. They’re in sprint planning, retros, demos—same as everyone else. Treat them like employees or they’ll act like contractors.

- Start with a Quick Win: Don’t give them a six-month epic. Assign a one-week bug fix that touches the full stack. Force them to push code to production fast. It builds confidence immediately.

- Before You Start: make sure your Master Services Agreement covers SOC 2, PII handling, and IP assignment. Do not skip this.

When It’s Not Working (And How to Fix It)

If your nearshore setup isn’t working, it’s usually one of these problems:

They’ve become a ticket queue: Your PMs throw tickets over the wall. The nearshore team builds exactly what’s in the ticket, even when it’s obviously wrong.

Fix: Pull them into discovery before tickets get written. Make it a rule—no work starts without a 15-minute kickoff between the PM and nearshore engineers. They need to understand the “why.”

They’re too quiet: Never speak up in stand-ups. Don’t challenge the designer’s mockups. Just say “yes” to everything. This is usually about confidence or culture, not competence.

Fix: Ask for their input directly. “Marta, you’ve worked with this API the most. What could go wrong here?” When a nearshore engineer spots a flaw in your plan, make a big deal out of thanking them. That’s how you build the psychological safety you need.

Track these monthly: PR cycle time, overlap hours actually used, escaped defects, and mean time to resolution.

A Product Team Structure That Won’t Break

The org chart you draw today creates the bottlenecks you’ll fight in six months. Worth thinking about now.

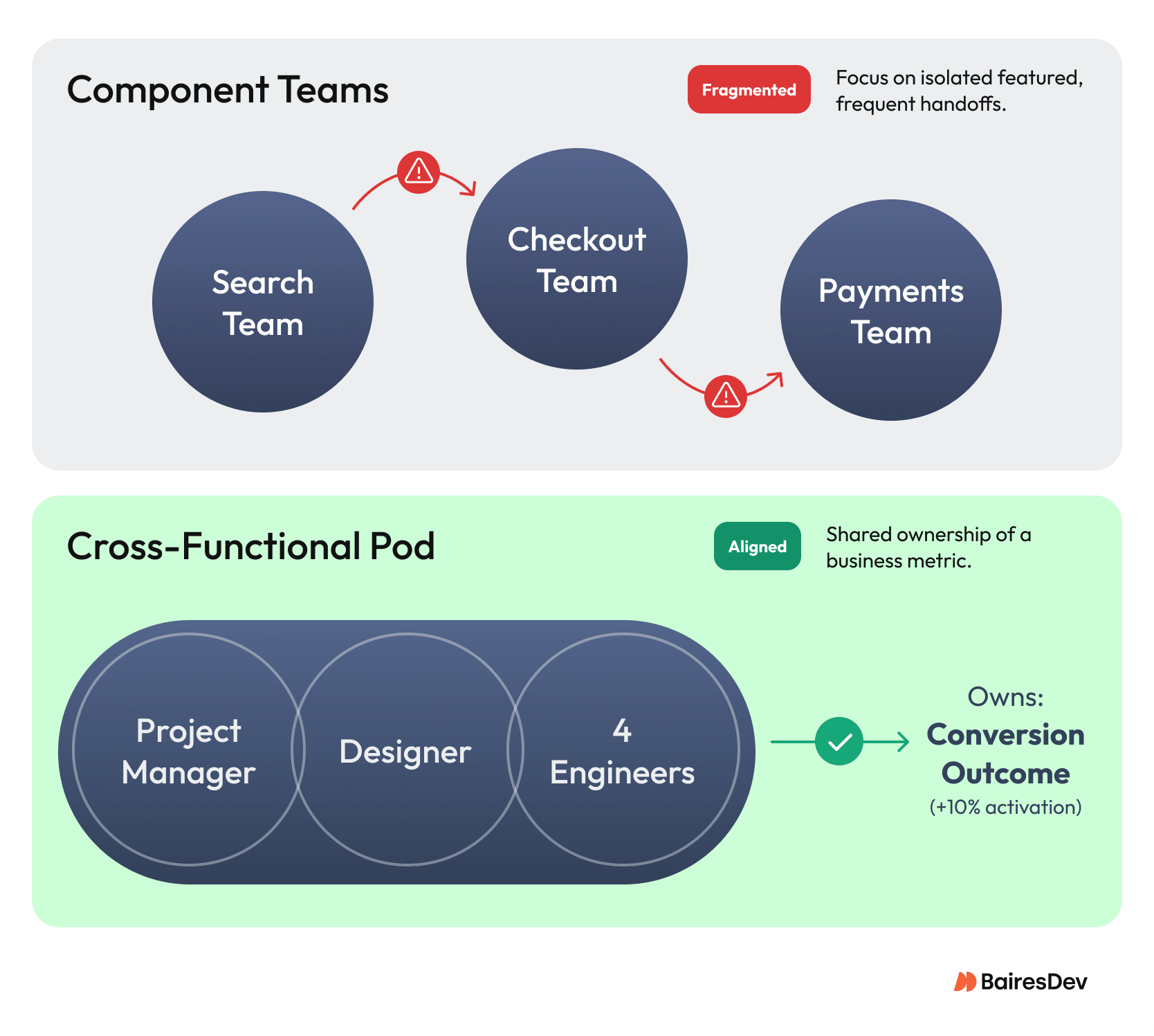

Most leaders default to organizing by component (e.g., “Search Team,” “Checkout Team”). This builds subject matter experts but destroys the user experience. Nobody owns the journey, just their slice.

The other trap: organizing by customer segment. “Small Business Team” and “Enterprise Team.” Good for customer empathy. Bad for efficiency.

The Empowered Pod

The solution? A cross-functional pod. This is a small, cross-functional team (1 product manager, one designer, 3-5 engineers, plus analytics support) that owns a specific customer problem, not the full feature backlog.

This matters a lot. You don’t create a “Checkout Team.” You create an “Onboarding Team” or a “Conversion Team.”

As a tech leader, this is how you stop being the bottleneck. You give the team a measurable outcome, a North Star metric like “improve new user activation from 20% to 30% in 90 days,” and let them figure out how.

That’s the theory, but making it work requires some structure.

How to Make Pods Actually Work

Autonomy without structure is chaos. You need a lightweight framework.

- Kill the 20-page Requirements Doc: Use a one-page brief instead and tie it to an OKR the pod owns. Intercom calls theirs an “Intermission,” but call it whatever you want. Three questions: What’s the problem? Why does it matter (to users and the business)? How will we know we succeeded?

- Run Discovery Sprints: Before any build sprint, the team (PM, Product designer, tech lead) spends a week de-risking the idea. They build a high-fidelity prototype and test it with 5-6 actual users. This is insurance against wasting three months on something nobody wants.

- Clarify Accountability: The PM owns the product vision, business outcome, and prioritization. The Product designer owns the user experience and problem framing. The tech lead owns the architecture and delivery. When everyone knows their lane, you stop having “who owns this?” debates.

Finally, have pods report monthly on three things: outcome progress, lead time, and dependency count.

That’s it. This is about ownership and dependencies. When pods own outcomes instead of features, you get less cross-team coordination overhead. Not zero, that’s not realistic, but less.

BairesDev Expert Perspective: Structure Only Works When People and Tools Are Aligned

I’ve spent more than ten years working on product teams across very different contexts, from startups with three people to organizations with hundreds of product practitioners. I’ve seen teams get built, dismantled, and merged, and through all of that, one pattern has held consistently: cross-functional pods are the most strategic structure I’ve worked with, but only when the right people and the right tools are in place.

Pods work because they align everyone around a shared outcome. They make it easier to collaborate with internal stakeholders, run experiments, and maintain a backlog that exists to serve a specific KPI rather than a list of features. When teams own outcomes, conversations shift from opinions to evidence, and progress becomes measurable.

But structure alone isn’t enough. I’ve seen people without formal titles deliver outstanding product work, and others with impressive credentials fail to make an impact. The difference is in mindset. The strongest product teams are made up of people who are humble but know how to say no, who rely on data but still go where the users are—talking to them, testing the product themselves, and validating assumptions in the real world. These are people who propose ideas, challenge decisions, listen carefully, and are genuinely enjoyable to work with.

But even great people struggle without the right tools. Product teams need systems that support their work: well-configured workflows in tools like Jira, access to user behavior data, and analytics support that helps teams understand whether they’re actually changing user patterns.

Ultimately, good tools can’t replace good judgment, but they can improve it. When structure, people, and tools are aligned around the same outcomes, product pods stop being an org chart idea and start becoming a true competitive advantage.

Get Out of Your Own Way

Building a product team is about designing a system that doesn’t need your input for every decision.

You have the playbook now: Hire for trajectory, not just pedigree. Deploy nearshoring for velocity, not cost savings. Architect cross-functional squads that own business outcomes, not just feature lists.

If you do this right, you move from being the bottleneck to being the architect. Your team builds, ships, and learns without you in the room. That’s when you know it’s working.