Executive Summary

This article examines whether 2026 marks a real inflection point for quantum computing. It explains why most quantum progress has remained theoretical, how architectures are diverging in practical value, and why neutral-atom systems are emerging as the most commercially relevant near-term model. The central argument is that the next phase of quantum progress will be driven less by physics breakthroughs and more by software, hybrid workflows, and application-layer integration.

For more than two decades, quantum computing has lived in a permanent state of anticipation. Each year seems to promise a breakthrough that will change everything, from breaking Bitcoin encryption and rendering modern cryptography obsolete, to accelerating the discovery of new drugs and materials beyond what classical computers can model.

Year after year, the impact has largely remained confined to research labs and conference keynotes. But times are changing fast.

Quantum architectures have crossed a threshold where real workloads, not just experiments, are starting to make sense. The question is no longer “Is quantum real?” It’s “What can quantum computing do for me?” And more daunting still, “Will I be ready for quantum?”

An IBM study found that 59% of executives believe quantum-enhanced AI will transform their industry by the end of the decade, but only 27% expect their organizations to be using quantum computing in any capacity by then, a gap IBM characterizes as a strategic miscalculation. Understanding what comes next requires separating hype from implementation and theory from practice. That starts with understanding how today’s quantum architectures work and where they create real value.

What Quantum Computing Models Actually Exist Today?

- Today’s quantum computing landscape consists of three primary approaches: gate-based quantum computing, quantum annealing, and neutral-atom systems. Each has distinct implications for scalability, cost, and applicability. These approaches also pose very different challenges when it comes to creating usable qubits.

1. Gate-Based Quantum Computers: The Long Game

Gate-based quantum computers use programmable quantum circuits composed of discrete logic operations and are designed to support universal, fault-tolerant quantum computation over the long term. This is the most conceptually familiar quantum model, operating through sequences of single- and two-qubit gates governed by quantum mechanics. This is the model pursued by juggernauts like Google and IBM.

These systems are foundational from a theoretical standpoint:

- Universal in theory

- Required for full fault-tolerant quantum computing

- Advancing meaningfully in error mitigation

From an operational perspective today, they are also:

- Extremely complex to build and scale

- Dependent on cryogenics and dense wiring

- Still far from running deep, economically meaningful circuits

In gate-based quantum computers, qubits are physically fabricated and permanently fixed in place.

They are built as microscopic circuit elements on a solid chip, typically using superconducting materials patterned through advanced semiconductor fabrication. Once the chip is manufactured, the number of qubits, their positions, and their connectivity are all locked in. You cannot rearrange them without building a new chip. This requires an expensive and highly specialized fabrication process that limits large-scale development to a small number of well-funded organizations with specialized manufacturing capabilities.

In gate-based quantum computing, the problem is expressed as a sequence of operations applied over time to a fixed set of qubits. Computation emerges from precisely timed gate operations and entanglement patterns rather than from the physical arrangement of qubits themselves. This places enormous emphasis on timing, error correction, and noise suppression, which is why gate-based systems focus so heavily on cryogenics and control electronics. This infrastructure is complex and costly to operate.

Last year, Google announced Willow, their latest gate-based processor, reporting a breakthrough in the field. Follow-on work from Chinese laboratories quickly demonstrated comparable superconducting processor designs, reinforcing how fast gate-based hardware concepts diffuse once published.

Gate-based quantum computing is likely to change the world enormously in the long term. However, for most organizations, it remains a strategic investment rather than an operational technology.

2. Quantum Annealing: Narrow but Practical

Quantum annealing is a quantum computing approach optimized for solving specific classes of optimization problems. Rather than running arbitrary circuits, quantum annealers solve optimization problems by encoding them into energy landscapes and allowing the system to relax toward low-energy states.

In practice, this approach is closer to metallurgy than mathematics. When forging a blade in traditional swordmaking, the cooling process matters as much as the heat. Controlled cooling allows the metal’s internal structure to settle into a stronger, more resilient form.

Quantum annealing follows the same physical principle. A computational problem is encoded as an energy landscape of peaks and valleys, where lower valleys represent better solutions. By changing this landscape slowly, the system has time to move toward deeper valleys rather than getting stuck early in shallow ones. If the process moves too fast, the system can freeze in a poor solution that appears stable but is actually suboptimal and hard to escape.

In both cases, the outcome is determined by how much time the system has to relax. Controlled cooling allows atoms in a blade, or qubits in an annealer, to settle into deeper, more stable energy states. Those states are physically more robust and computationally correspond to higher-quality solutions.

Quantum annealing deserves a more grounded treatment than it often gets. While it is not a universal model of computation, it is already delivering value for specific classes of problems when used correctly.

D-Wave, a quantum computing company, has made annealing available through the cloud as part of quantum-hybrid workflows, where classical preprocessing and postprocessing are combined with quantum optimization runs. This hybrid approach matters. Most real-world optimization problems are too large or noisy to be solved by quantum hardware alone, but they can benefit significantly when quantum resources are used to explore complex energy landscapes.

Annealing workflows are useful for problems such as:

- Traveling salesman variants

- Vehicle routing

- Workforce scheduling

- Portfolio optimization

- Constraint-heavy allocation problems

Leveraging quantum annealing today can lead to meaningful efficiency gains, not by replacing classical solvers, but by accelerating the hardest parts of the search. In published case studies, hybrid quantum annealing has reduced solution times or improved solution quality compared to purely classical heuristics.

Annealing can deliver value today, but only when the problem fits its shape. It is most effective for static optimization problems and becomes inefficient when applied to highly dynamic or logic-heavy workloads.

3. Neutral-Atom Quantum Computing: The Breakout Star

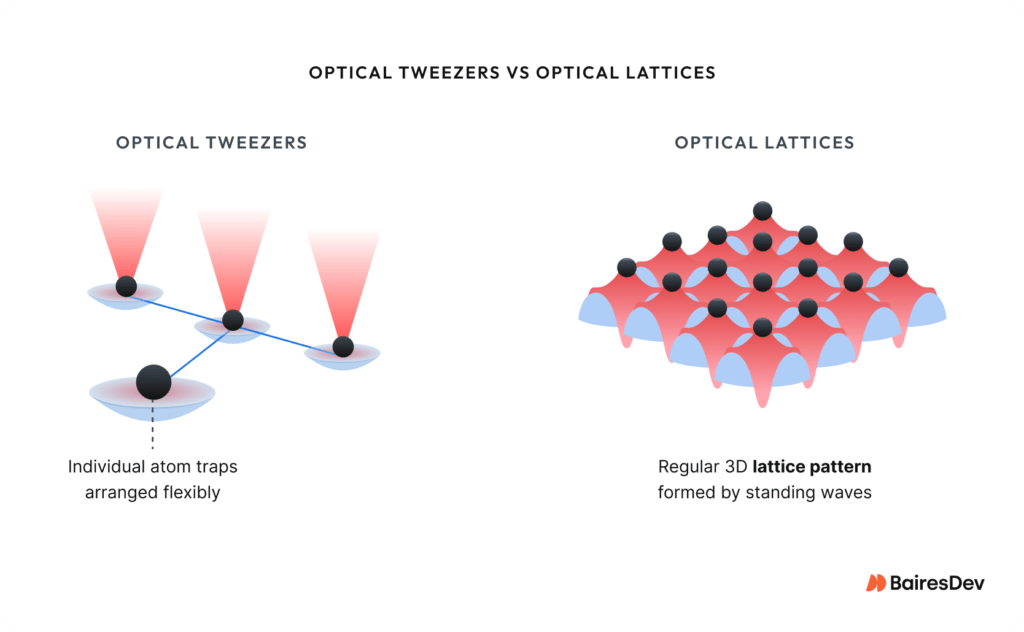

Neutral-atom quantum computing uses individual atoms, trapped and controlled by lasers, as programmable qubits arranged through physical geometry rather than fixed wiring. Neutral-atom systems sit between gate-based and annealing approaches, and this is where momentum is building.

Instead of superconducting circuits or frozen hardware graphs, neutral-atom quantum computers use individual atoms trapped by lasers, arranged into programmable geometries, and controlled optically. By leveraging optical tweezers or lattices, atoms can be positioned precisely by light alone, allowing interactions and constraints to be defined through dynamic geometry rather than static wiring. Leading companies in this space include Atom Computing, QuEra, Pasqal, and Infleqtion.

What makes this approach compelling isn’t novelty, it’s scalability and structural alignment with real problems.

How Neutral-Atom Quantum Systems Work

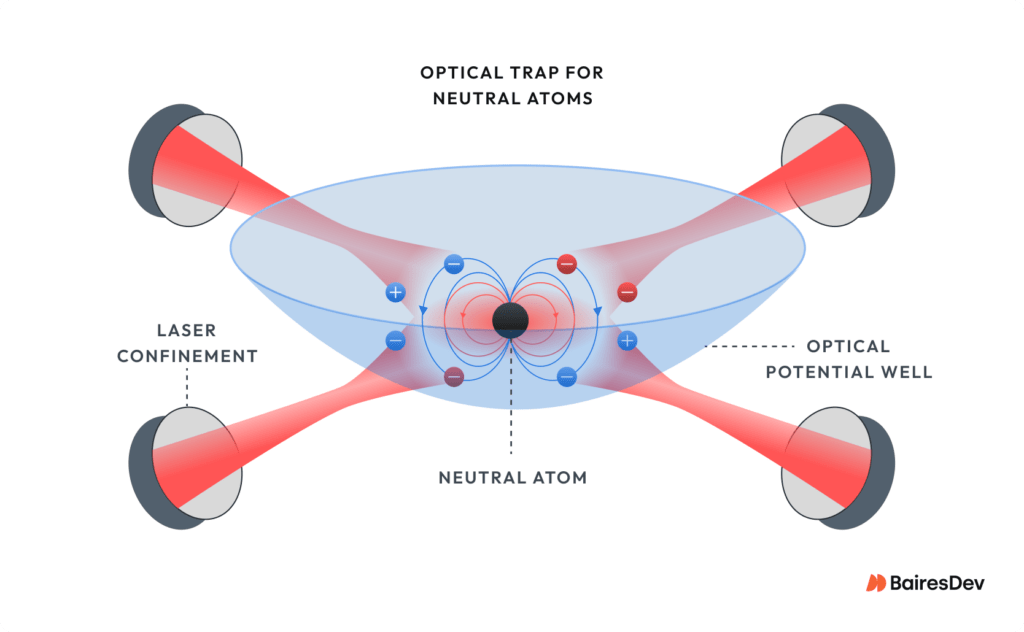

Using precisely calibrated laser fields, these systems trap atoms and operate in a room-temperature vacuum environment. Laser cooling and optical trapping reduce atomic motion to nanokelvin scales locally without cooling the entire machine to near absolute zero.

This distinction matters. Cryogenic systems require extreme thermal control, dense wiring, and highly specialized fabrication. Neutral-atom systems, by contrast, confine atoms using conservative optical potentials. These “energy bowls made of light” trap each atom with nanometer precision.

The result is long coherence times without refrigerators, fewer physical scaling bottlenecks, and hardware that grows by adding optical complexity rather than electrical infrastructure. Scaling becomes an optics and control problem, not a refrigeration and wiring problem.

Neutral-atom systems scale differently:

- Qubits are identical by nature.

- Control scales with optics, not wiring.

- Connectivity is programmable through geometry.

Understanding Where The Complexity Lives

In neutral-atom systems, qubits are naturally identical and individually addressable. There is no need to fabricate slightly different components and compensate for manufacturing variation at the hardware level. Instead, individuality is introduced through software: frequency offsets, spatial addressing, pulse shaping, and timing.

This shifts a significant portion of the scaling problem from PhD-level hardware engineering to control software, calibration layers, and orchestration logic—domains where modern software practices are far more effective.

This architectural shift opens the door to tighter integration with AI-driven tooling. Calibration, pulse optimization, error mitigation, and hybrid classical-quantum workflows are all areas where machine learning can accelerate progress. Rather than hard-coding control strategies, neutral-atom platforms can increasingly rely on adaptive software systems that learn how to best exploit the underlying hardware.

Neutral atoms don’t just benefit from advances in ML and AI. They may be one of the first quantum architectures where machine learning becomes a core part of the control and application stack.

As the focus shifts from hardware to software, the center of gravity moves toward abstraction, orchestration, and integration. Once qubits can be reliably trapped, addressed, and entangled, the differentiator is no longer the physics alone, but how effectively that raw capability is exposed to developers and enterprises.

Control planes, scheduling layers, data pipelines, and domain-specific modeling tools become the real bottlenecks.

This is where neutral-atom systems are especially well positioned. Because complexity is already expressed in software rather than hardware, higher-level tooling can evolve rapidly. Workloads can be composed, optimized, and iterated without redesigning physical machines.

Over time, the winners in this space will be those who build robust application stacks on top of quantum hardware and translate abstract quantum capability into concrete business outcomes.

Why Geometry Matters More than Raw Qubit Count

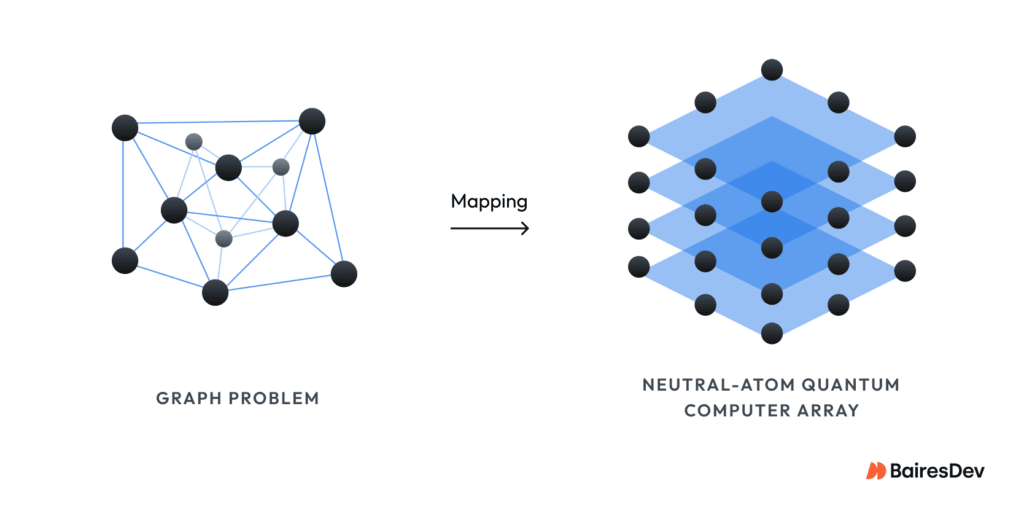

- Geometry matters more than raw qubit count because many real-world problems are defined by relationships, constraints, and structure rather than numerical operations. Systems that can encode those relationships directly gain an advantage that sheer qubit quantity alone cannot provide.

Many of the hardest problems in science and industry are not arithmetic. They are relational.

Examples include:

- Molecular structures and reaction pathways, where energy states depend on spatial configuration

- Protein interactions and folding dynamics, driven by complex interaction graphs

- Supply chain dependencies, where delays propagate across networks of suppliers and constraints

- Scheduling in manufacturing, airlines, and workforce planning

- Network optimization in telecommunications, logistics, and energy grids

- Combinatorial search problems such as maximum independent set, graph coloring, and constraint satisfaction

A concrete example already explored on neutral-atom platforms is the Maximum Independent Set (MIS) problem. Imagine planning seating for a wedding where certain guests cannot sit near each other. The MIS problem is finding the largest group of guests you can seat without putting any incompatible pair too close together.

MIS appears in contexts ranging from wireless frequency allocation to scheduling and resource conflict resolution. Nodes represent tasks or resources, and edges represent conflicts. The goal is to select the largest set of non-conflicting nodes, a problem that becomes prohibitively difficult for classical solvers as graph size and density increase.

Neutral-atom systems are well suited for this class of problems because the hardware can directly encode the graph. Atoms represent nodes, and Rydberg interactions represent edges. Constraints are enforced physically through interaction geometry rather than indirectly through software penalties.

Early demonstrations show that this approach can explore solution spaces efficiently, especially when combined with classical preprocessing and hybrid optimization techniques.

Neutral-atom systems excel when problems are better described as graphs than equations:

- Qubits can be physically arranged to mirror graph structure.

- Interactions encode constraints directly.

- Distance and adjacency are native concepts, not abstractions.

This represents a fundamentally different programming model than forcing graphs into fixed hardware layouts or dense wiring topologies.

All of this matters most when problem structure is the bottleneck. Few domains illustrate that better than drug discovery, where progress depends less on raw computation and more on navigating vast, constraint-heavy search spaces.

When Does Quantum Computing Become Useful for Drug Discovery?

- Quantum computing becomes useful for drug discovery when it can improve search and simulation for specific molecular interactions, rather than replace classical computation entirely. Near-term value comes from hybrid workflows that combine classical machine learning with quantum systems to evaluate complex interaction structures more efficiently.

Drug discovery is often cited as the apex of future quantum applications, but the reason neutral atoms are interesting here is not “faster compute.” It’s “better search.”

Drug discovery involves navigating enormous chemical spaces, understanding subtle interaction energies, and narrowing down infinite potential candidates efficiently.

Neutral-atom systems are particularly well suited for:

- Quantum simulation of molecular systems

- Evaluating interaction graphs

- Hybrid workflows where classical ML proposes candidates and quantum systems evaluate physical feasibility

What makes neutral-atom systems compelling in the near term is not raw computational replacement, but their ability to embed problem structure directly into the computation itself. By doing so, they change the economics of search and optimization in ways that classical approaches often cannot.

For complex, high-dimensional problems, neutral-atom systems are poised for a breakout year.

Why Skepticism Matters in Frontier Quantum Research

- Skepticism matters in frontier quantum research because early experimental results are often fragile. They are difficult to reproduce and highly sensitive to interpretation. In this environment, promising signals can be mistaken for scalable breakthroughs.

There is no shortage of excitement around the future of quantum computing, and healthy skepticism is essential when evaluating claims at the edge of both physics and commercialization.

Over the past year, many technology leaders’ feeds were flooded with headlines about Microsoft and its work on topological qubits and Majorana-based approaches. These ideas are intellectually elegant and deeply interesting from a theoretical physics standpoint. They offer a futuristic, paradigm-shifting approach to quantum computing.

But the reaction within the broader physics community has been openly critical.

A number of experimental physicists have publicly questioned whether the signals attributed to Majorana modes actually demonstrate what is being claimed, or whether they can be explained by more conventional effects. Some have gone further, calling the interpretations premature—or outright unsupported by available data.

The debate is not new. In 2018, a paper in Nature claiming evidence of Microsoft’s Majorana modes was later retracted, sparking controversy and justifying renewed skepticism of their 2025 findings.

This highlights a recurring challenge in frontier research: distinguishing between suggestive experimental signatures and reproducible, commercial-ready systems.

From an empirical perspective, the concerns are consistent:

- Experimental evidence remains fragile and difficult to reproduce.

- Results are highly sensitive to interpretation.

- Timelines for scalable, fault-tolerant systems remain deeply uncertain.

- Even optimistic roadmaps place impact well beyond the next several years.

None of this diminishes the scientific value of the work. Breakthroughs in physics often emerge from long, contested research paths.

These approaches are worth watching academically. They are not where near-term commercial leverage, platform development, or application-layer innovation is likely to come from.

Is 2026 A Turning Point for Quantum Adoption?

- 2026 is not a turning point in the sense of broad disruption or replacement of classical computing. However, it does mark a shift toward practical adoption in specific domains where quantum systems can be operationally useful.

2026 does look like a year where:

- Neutral-atom platforms move from experimental to commercially available.

- Hybrid classical-quantum workflows begin to meaningfully impact optimization problems.

- Early adopters gain advantage by engaging before stacks are standardized.

The Skills Gap

One of the least discussed barriers to quantum adoption is not hardware, but people.

Most experienced software engineers have never encountered the constraints that define quantum computation. In classical systems, variables can be copied freely, reused, and overwritten. In quantum systems, qubits cannot be cloned, measurements destroy state, and variables often map one-to-one with physical qubits. Algorithms must be designed with these constraints in mind from the start.

Today, quantum software development happens through specialized frameworks rather than low-level hardware control. Toolkits such as Qiskit, Cirq, and PennyLane allow developers to define quantum circuits, simulate execution, and target different backends without writing hardware-specific code. These frameworks abstract away many physical details, but they also introduce new constraints that require developers to think differently about data flow, state management, and algorithm design.

High-performance quantum emulation is also playing a critical role in upskilling developers today.

Quantum emulators allow teams to design, test, and debug quantum algorithms on classical hardware. While they do not deliver quantum optimizations in production, they provide something equally important at this stage: familiarity. Engineers can learn how quantum programs behave, how constraints affect algorithm design, and how hybrid workflows are constructed.

Systems such as the Atos Quantum Learning Machine are designed specifically for this purpose. They simulate quantum processors and execution models inside an HPC environment, allowing organizations to develop skills, tooling, and quantum intuition without waiting for expensive production hardware.

Using Quantum Today

Cloud-based access to quantum systems is already allowing practical experimentation. Platforms such as AWS Braket provide managed access to multiple quantum backends, including gate-based processors, quantum annealers, and simulators, all integrated into familiar cloud workflows. This allows quantum execution to be incorporated into existing pipelines rather than treated as a standalone research exercise.

In addition to Braket, major cloud providers now offer managed quantum services through platforms such as Azure Quantum, Google Quantum AI, D-Wave Leap, and IBM Quantum Cloud. IBM also develops and maintains Qiskit, the most widely used open-source software framework for quantum computing. These platforms connect emerging quantum models through familiar interfaces, lowering the barrier to access.

In practice, quantum systems are rarely used in isolation. Classical infrastructure handles data preparation, orchestration, and analysis, while quantum hardware is applied selectively to the parts of the problem where it provides leverage. For many organizations, this hybrid cloud model represents the most realistic entry point today, enabling exploration without committing to highly specialized infrastructure.

Final Thoughts: Where The Real Shift Is Happening

Quantum computing will not arrive as a single breakthrough moment. It will arrive through new architectures solving old problems better than existing hardware can. Neutral-atom systems are emerging as one of the first places where that alignment is real, where the focus shifts from whether the hardware works to how we build on top of it. The most important change ahead isn’t in lasers, refrigeration systems, traps, or qubits. It’s in software.

As core hardware challenges stabilize, the bottleneck moves to:

- Application modeling

- Workflow orchestration

- Hybrid classical-quantum data pipelines

- Control planes and abstractions

- Integration with existing data, ML, and enterprise systems

The companies that win won’t just have powerful quantum hardware. They’ll have usable stacks that let developers and enterprises turn raw quantum capability into business outcomes. That’s the phase we’re entering now—where progress is measured less by breakthroughs in physics and more by the software we build to make emerging quantum hardware usable. The real question is not whether quantum computing is coming. It is whether your organization is prepared to engage with it.

Is your company ready for quantum?