When a Rails team hits 10 developers, velocity drops. Features that took 2 weeks now take 5. Bugs in checkout break user profiles. New hires need months to ship confidently. The culprit? Business logic tangled into models and controllers.

In this article, we identify the symptoms of mixing business logic into Rails’s implementation of MVC, call out the implications, and enumerate practical solutions to keep core Rails code separate from domain logic. Clearly delineated code speeds development, debugging, and delivery.

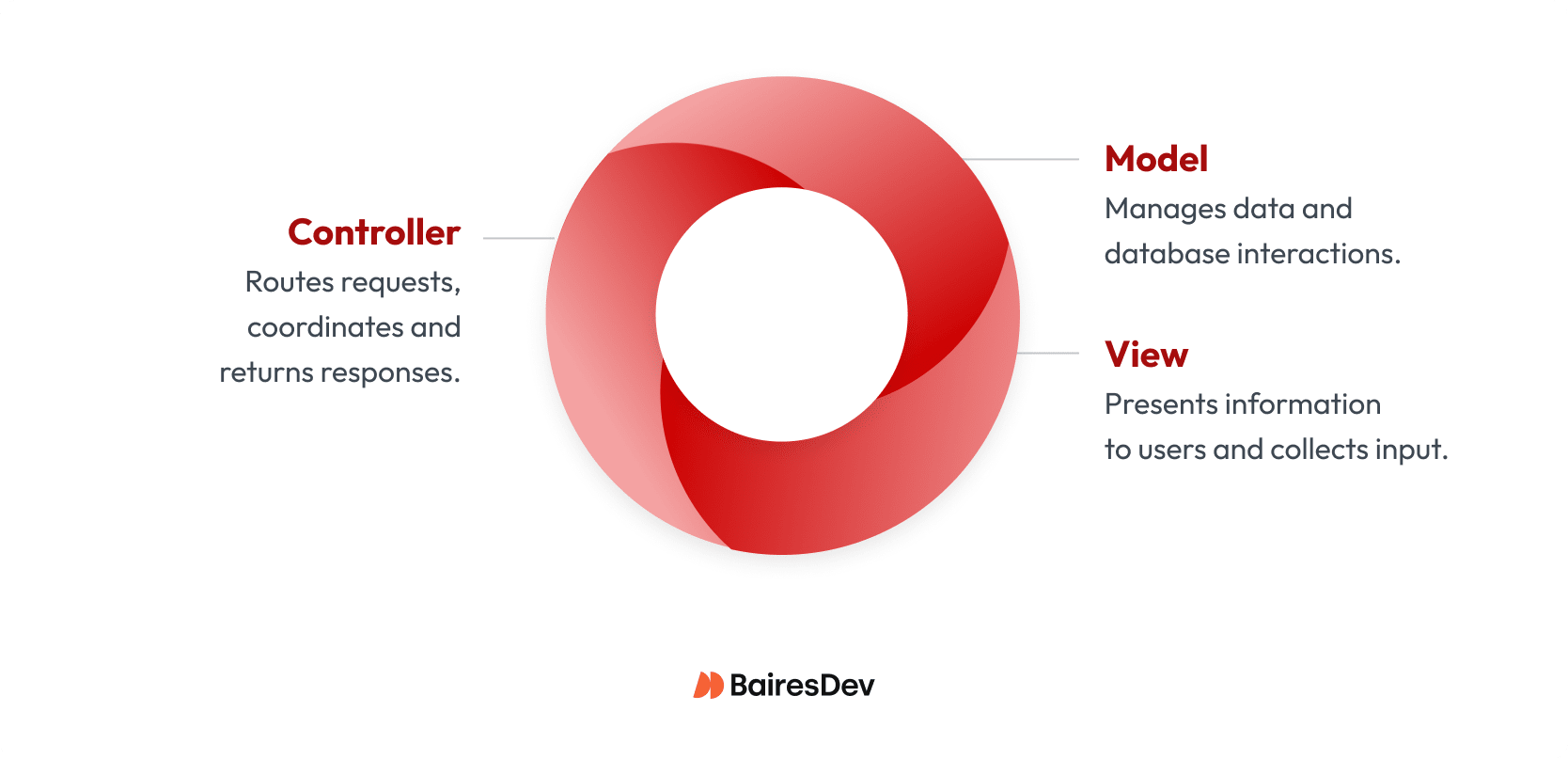

MVC in Rails: A Quick Refresher

Rails implements the Model-View-Controller design pattern (or MVC) in Ruby. MVC divides the logic of an application into three concerns:

- Models represent items in the system

- Views present information and collect input

- Controllers liaise between the user or API to facilitate change

For example, User is an oft-used model to represent an identity. A login and checkout form are common views. A prospective OrderController receives requests, creates and modifies orders as directed, affects model state, and presents an updated view in response.

While MVC describes logical boundaries for implementations and Rails provides a closely-aligned framework to organize code into the three concerns, neither MVC nor Rails enforces separation.

Further, MVC provides no unique concern for business logic, or those processes, steps, and rules the enterprise wants to express as an application. Without vigilance, it is easy for developers to blur the distinctions between M, V, and C, and worse, disperse domain logic throughout each concern.

Fat Models & Controllers and Sprawling Views

In Ruby on Rails, a concern is considered overloaded or “fat” if it contains any code or logic unrelated to its intended and specific role.

For example, a Rails model is fat if it does any of the following:

- Orchestrates the creation or mutation of other models

- Transforms itself into a different model or object

- Provides helper functions to render a view

- Embeds a business rule not specific to its responsibility

Similarly, a Rails controller is fat if it:

- Contains any business logic

- Constructs extensive context to render a view

- Executes a long-running computation

- Calls a third-party API or an internal API with moderate or long latency

A view is fat if it:

- Performs any domain logic

- Depends on external state information not provided by the controller

- Mutates any model or causes any side-effects

- Queries a data source

Each case violates the Single Responsibility Principle (SRP), a software development tenet that holds that each unit of code should be purpose-built for a solitary task. Put another way, each unit of code—here, a Ruby class or subclass of a Rails class—should perform one job well, “[collecting] the things that change for the same reasons.”

For instance, consider the role of a model. If a model’s justification is solely to read and write valid records from a specific table in the database, creating a record in another table should be considered far out of its bounds.

Rails’s many powerful tools, especially model validations and life-cycle callbacks, seemingly encourage conflation of responsibilities. Rails teams must resist. The more expansive a unit of code becomes, the more difficult it is to comprehend, write tests for, and maintain. For stateless utilities a class method can work.

An Overly Ambitious Model

Let’s look at an example of a Rails model that’s too extensive and how to refactor the code to make it better conform to object-oriented programming principles and the SRP.

The Rails model code below represents an end-user in a system. It enforces a number of data consistency rules via Rails validations. To avoid reinventing authentication, password encryption, and secure tokens, it leverages Rails’s own `has_secure_password` and `has_secure_token`.

1class User < ApplicationRecord

2 has_secure_password

3 has_secure_token :activation_token

4

5

6 # Validations

7 validates :birth_date, presence: true

8 validates :email, presence: true, uniqueness: true

9 validate :strong_password

10 validate :age_must_be_over_18

11

12 # Scopes

13 scope :active, -> { where.not(activated_at: nil) }

14

15

16 # Business Logic

17 def activate!

18 update(activated_at: Time.current)

19 end

20

21 def activated?

22 activated_at.present?

23 end

24

25 def full_name

26 [first_name, middle_name, last_name].compact.join(' ')

27 end

28

29 private

30

31 def strong_password

32 unless password =~ /(?=.*[A-Z])(?=.*[a-z])(?=.*\d).{8,}/

33 errors.add(:password, "must be at least 8 characters and include upper/lowercase letters and a number")

34 end

35 end

36

37 def age_must_be_over_18

38 if birth_date.present? && birth_date > 18.years.ago

39 errors.add(:birth_date, "You must be at least 18 years old")

40 end

41 end

42endConsidering the characteristics of a fat model listed in the previous section, it’s plain this code is too broad and violates the single responsibility principle in three ways.

- The Rails validation named `strong_password` enforces what characters a password may contain. This implements business logic not germane to the persistence of user data, and is likely subject to change. Additionally, if the application has another form of user, such as an Administrator, the `strong_password` validation would likely apply to both. The validation is best extracted and made central as domain policy.

- Similarly, the validation `age_must_be_over_18` is another business rule better enforced by the domain, not the User model. It too is a candidate for separation.

- While `full_name` is computed directly from the attributes of the model (assuming `first_name`, `middle_name`, and `last_name` are columns) and is useful, it is orthogonal to reading and writing records to the underlying table. This method is best relegated to a decorator class (sometimes called a presenter class).

Refactoring the Model for Better Intent

Extracting the four methods listed above from the User model would narrow its purpose. Moreover, and adhering to the tenet of the SRP, it’s best to create multiple new Ruby classes: one to enforce the business rules for `User`, one to decorate the model to display a full name, and another to generate a legitimate activation token.

All provide a self-contained service. Indeed such classes are commonly referred to as service classes or service objects and sport names reflective of each object’s intent, such as `SaveUser` and `DecorateUser`. This is the service object pattern we use to keep domain logic out of models and controllers.

Omitting the latter two classes for brevity, `SaveUser` might be written as concisely as:

1class SaveUser

2 attr_reader :user

3

4

5 def initialize(user)

6 @user = user

7 end

8

9 def save

10 valid? && user.save

11 end

12

13 private

14

15 def valid?

16 user.valid? &&

17 Password.valid?(user.password) &&

18 Age.valid?(user.birth_date)

19 end

20endThis code assumes password and age validation are performed by domain methods `Password.valid?` and `Age.valid?`, respectively, implemented as class public methods. Push steps into private methods so orchestration remains readable.

`SaveUser` now has a singular purpose: Save a `User` record if it passes the model’s own Rails validation rules and the business’s rules for password composition and age. Most services expose a simple entrypoint such as def call to coordinate the workflow.

Given `SaveUser` exists as a Rails service object, the User model can be refocused and narrowed. Controllers invoke a single call method so actions stay small and testable.

1class User < ApplicationRecord

2 has_secure_password

3 has_secure_token :activation_token

4

5

6 # Validations

7 validates :birth_date, presence: true

8 validates :email, presence: true, uniqueness: true

9

10 # Scopes

11 scope :active, -> { where.not(activated_at: nil) }1endIn a full refactor, the activation logic is moved to a dedicated service object, and the status check is handled via the scope or a decorator. The model remains lightweight and implements no business rules.

Applying the Pattern to Controllers and Views

Refactoring the model is only the first step. When developers aggressively clean up models, the displaced business logic often tries to migrate into Controllers or Views. To maintain a truly clean architecture, we must apply the same separation of concerns to the rest of the MVC stack.

The Burdened Controller

Controllers often become dumping grounds for logic that doesn’t fit neatly into a model. For example, a “fat” checkout controller might attempt to process payments, update inventory, and trigger email notifications all within a single method. This makes the controller difficult to test and ties the request handling logic too tightly to backend processes.

To fix this, we move the orchestration into a Service Object (e.g., ProcessOrder). The controller returns to its primary job: handling the HTTP request, calling the service, and rendering the appropriate response based on success or failure. The controller no longer needs to know how a payment is processed, only that it was processed.

The Sprawling View

Views should be “dumb,” as their only job is to present data. A “fat” view often violates this by including logic to query the database (e.g., counting orders to see if a customer is a VIP) or complex formatting rules. If the definition of a VIP changes, developers are forced to hunt through HTML templates to update the logic.

We can clean this up using the Decorator pattern (also known as a Presenter). A Decorator wraps the model and encapsulates the logic for presentation. Instead of the view calculating VIP status, it simply asks the decorator for the answer. This keeps the view file clean and semantic, while the logic remains testable in a plain Ruby object.

Objects for Everything Else

While Rails is based on the MVC pattern (as implemented by the classes `ApplicationRecord` and `ActionController::Base` and the module `ActionController::Rendering`, respectively), a Rails application is not limited to objects representing database tables, user interfaces, and controllers.

Rails itself includes specialized classes and modules to send and receive email, manage background jobs, and provide a consistent global identifier for every record.)

Rails application code can be extended to include any number of custom Ruby classes and modules. The service class `CreateUser` is just a Plain Old Ruby Object (PORO) tailored to coordinate and implement a specific use case within the application. Keep domain objects separate from the data layer to preserve SRP.

In addition to orchestration, a PORO can control access, filter data, and compose other objects. Use value objects for immutable concepts like Money or Email.

- Authorization: It’s common for a multi-user application to limit access to processes based on a user’s identity, role, or express permissions. For example, editing a policy might be limited to only users with a valid license. A policy object can encapsulate access rights. Given a user, the object can return a set of permissible operations.

- Scope: Akin to authorization, a multi-user or multi-tenant application typically limits access to data. Files belonging to one organization cannot be cataloged, read, or modified by another organization. Purview in Rails is called a scope. Given an entity—perhaps a user, organization, or even another server—a scope object can compute the set of readable records.

- Aggregation: Every application mutates its data. Data is displayed via a form or an API response and is acted upon by an end-user or an API request. Simple Create-Read-Update-Delete (CRUD) operations may align a model closely to a single form or API request, but those are exceptional cases. Single-page web applications (SPAs) and mobile apps routinely consume amalgams of data for efficiency. The request generated by a complex form might affect multiple models.

A form object can be crafted and shaped to fit specific input or output requirements. As an example, consider a form to file an auto insurance claim. It would contain driver, location and vehicle information for ease-of-use. A PORO object, perhaps named AutoInsuranceClaimForm, could capture all the fields. (Another PORO service object would transform and persist the data into the proper tables.)

- Inquiry: Another use of input is to search. A query object represents search parameters and results. Think of a query object as a kind of liaison between criteria and one or more models.

Both a form object and a query object can also validate parameters and verify access (using policy objects), keeping controllers “skinny”.

Not every use case requires its own set of custom supporting objects. In fact, given an amassed collection of fine-grained PORO actors, complex sequences can be constructed by combining, interweaving, and composing existing objects.

Good Governance is as Important as Good Code

Rails famously prioritizes convention over configuration (CoC). Rails has plenty of options to fine-tune application behavior, to be sure (it supports many databases, supports multiple deployment environments, and provides for structured logs, among others), but the overall structure of every Rails application is the same.

- Each Rails application has its own “root” directory somewhere in the file system

- Within the project root, the subdirectory app/models contains model classes (the M of MVC); app/controllers contains controllers classes (the C); and app/views contains the project’s layouts and templates (the V)

- Within the Rails root, the subdirectory config contains YAML and Ruby files to customize the behavior of Rails

- Files inside db defines the application’s database schema

- test or spec, for Minitest and RSpec, respectively, contain automated tests.

There are other standard directories, and a team can extend the Rails foundation to add its conventions. As an example, many teams put decorator objects in app/decorators.

The namespaces and class names used for local practices are as important as the use of conventions. Organize folders and files into hierarchies to reflect responsibilities. Good governance of a source repository makes it easy for developers to navigate and read existing code and review and critique new code.

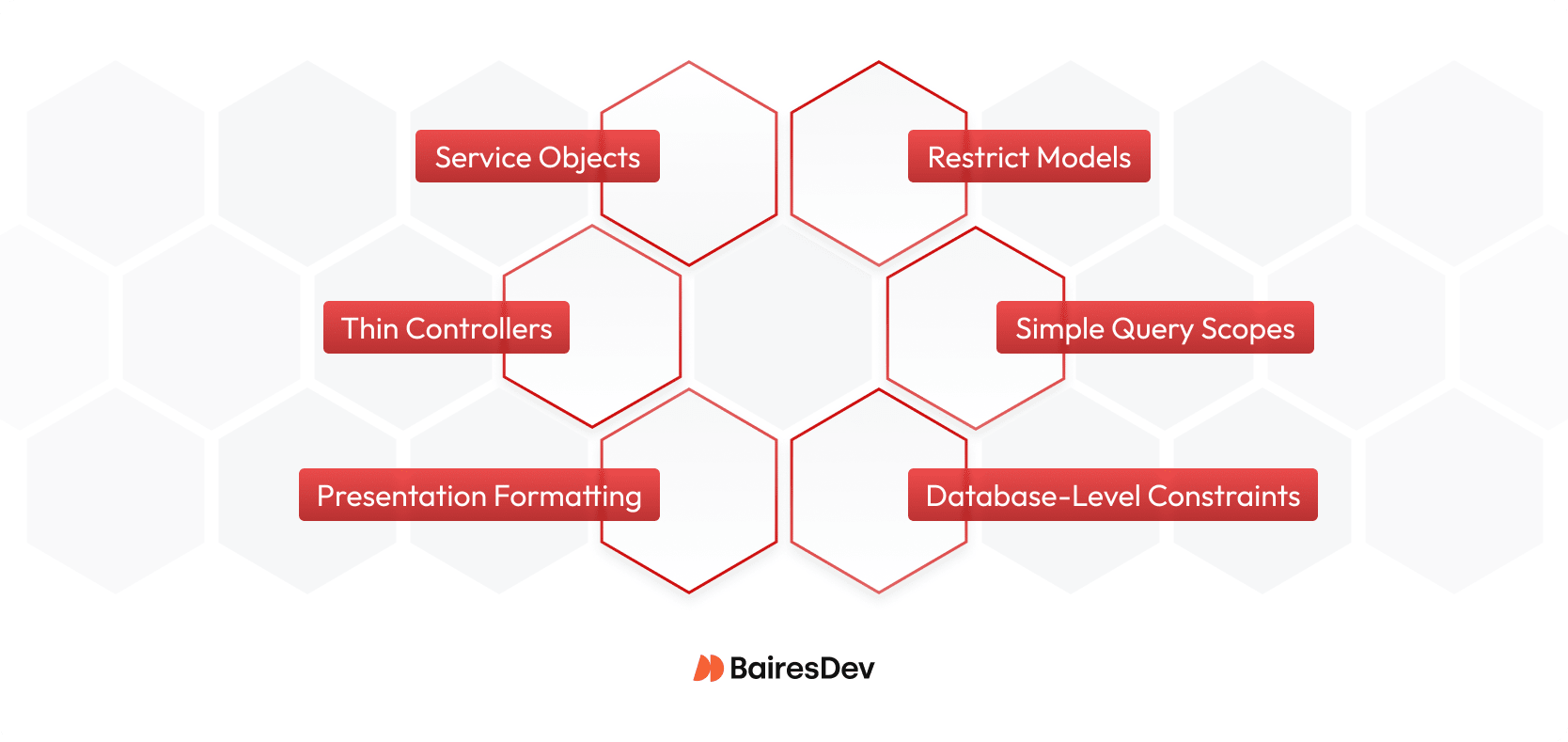

Best Practices for Rails Applications

First and foremost, mind the Single Responsibility Principle. Measure your code against it and refactor to keep your classes and modules focused, short, and reusable.

Here are some additional simple rules to improve the maintainability of Rails applications. Each rule can be adopted immediately for new code and retrofitted to existing code as ongoing refactors.

- Narrowly restrict a model to only save, read, and update operations, including state, validation, and normalization.

- Keep scopes simple within each model, restricting those scopes to columns defined solely in the model.

- Enforce Rails uniqueness constraints, manage foreign keys, and speed queries using database indices wherever possible.

- Separate a model’s presentation-specific logic into its own decorator.

- Limit each controller to read and validate a request and assemble a response.

- Delegate all domain logic—input processing, transactions, and interaction with other systems—to either a service object or a Plain Old Ruby Object (PORO). For stateless utilities a class method can work.

Ride Ruby on Rails

Rails is an incredibly powerful, robust, performant, and stable development platform. Like Ruby itself, Rails makes developers happy and productive.

Clean architecture pays dividends when you’re scaling a team or accelerating delivery. Service objects and POROs reduce onboarding time, limit the blast radius of changes, and keep feature work moving in parallel. The upfront discipline of separation prevents the technical debt that slows teams down after a few quarters.

Combine Ruby, Rails, the Single Responsibility Principle, and a modicum of vigilance to make the entire extant and future development organization happy and productive.