Architecture decisions shape how fast your teams ship, how often you get paged on Sunday, and how much of your budget disappears into operational overhead for the next two to three years. Selecting among software architecture patterns is a big bet on your organization’s capabilities.

The question isn’t which architecture pattern is best. It’s which pattern your team can actually operate.

This guide covers scalable backend architecture patterns: monolithic and layered architecture, microservices architecture, event-driven architecture, CQRS with event sourcing, and space-based architecture. The focus here isn’t on implementation details. Instead, we’ll examine when each pattern actually reduces risk versus when it creates complexity your development and operations teams can’t absorb.

For deeper implementation guidance, Microsoft’s architecture center offers solid reference material.

The Question Nobody Asks First

Most architecture debates start wrong.

Teams argue monolith versus microservices like it’s a religious question. It’s not. The real question is simpler and harder: what level of operational complexity can your organization actually sustain while still shipping value?

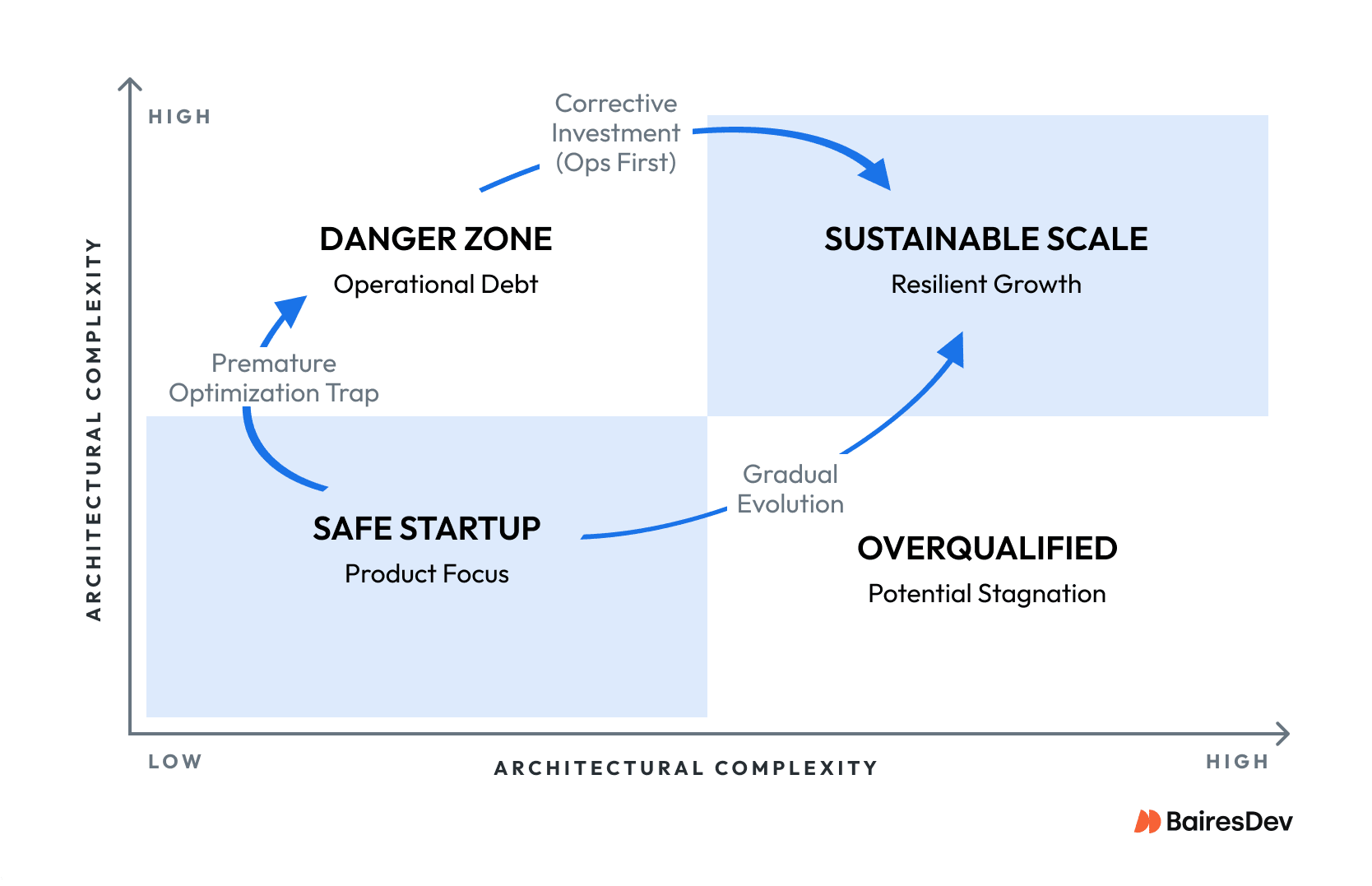

Consider a VP of Engineering at a high-growth Series C fintech. Good platform team. They’d run a well-structured monolith successfully for four years. New CTO arrives, reads some blog posts, decides microservices architecture is the future. Eighteen months into migration: three backend services decomposed, massive operational debt, feature delivery down forty percent. The architecture pattern was technically superior. The organization lacked monitoring tools, automated testing infrastructure, and DevOps maturity to run it.

That story repeats constantly. Teams adopt sophisticated architectural patterns before building foundations. Then you get distributed monoliths, alert fatigue, and engineers debugging infrastructure instead of building products. When error handling spans dozens of services and cross-cutting concerns require coordination across teams, operational overhead compounds fast. Without solid design patterns for loose coupling, the entire system turns fragile.

The opposite problem exists, too. Organizations cling to monoliths long after team coordination became the bottleneck. When adding new features requires synchronizing five teams through a two-week release train? Your software architecture is now blocking business growth.

Architecture decisions match system structure to organizational capability. A scalable architecture pattern that accelerates Stripe might paralyze your Series A startup. Context is everything.

The Patterns (What Actually Matters)

Each architecture pattern below is examined with emphasis on operational reality. Some sections are longer than others. That’s intentional, as the patterns that cause the most confusion get more attention.

Monolithic and Layered Architecture

Monolithic architecture deploys everything as a single unit. Layered architecture organizes that unit into tiers: presentation, business logic, data access. These design patterns remain the baseline for most software systems.

They’re underrated.

Single deployment artifact. Linear debugging. Faster engineer onboarding. Strong data consistency since all system components share one data storage layer. For teams under twenty engineers working moderate complexity domains, these architectural patterns deliver the fastest path to production. You get solid system stability without the overhead.

Constraints show up at scale. Multiple teams hitting the same codebase means merge conflicts and release coordination nightmares. Independent scaling isn’t possible. Failures cascade across the whole application.

But here’s what nobody tells you: a well-structured monolith with proper modular boundaries, automated testing, and deployment automation can scale further than most teams think. Shopify ran a monolith serving millions of merchants until relatively recently. Basecamp still does. As Martin Fowler notes, almost all successful microservice stories started with a monolith that got too big. The trigger for migration should be demonstrated pain, not architectural fashion.

For organizations under fifty engineers, this architecture pattern remains the right default. It’s a proven solution for many scalable systems.

Microservices Architecture

Microservices decompose applications into independent services, each owning a bounded capability. Services communicate through APIs, maintain their own data stores. Loose coupling between services enables parallel development. An API gateway pattern handles client requests while managing cross-cutting concerns.

When does this actually work? When org structure aligns with service boundaries. Teams own services end-to-end. Independent scaling matches resource utilization needs. Multiple services evolve at different paces.

The operational demands though. Each service needs its own deployment pipeline, monitoring config, runbook. Distributed tracing becomes essential. A load balancer distributes traffic, but inter-service communication has to handle failures gracefully. Data consistency requires sagas or eventual consistency. Managing data models across boundaries needs careful planning.

In our experience advising platform teams, most underestimate this. They have perhaps two of the six prerequisites in place and wonder why everything feels harder.

The prerequisites:

- Robust automated testing at unit, integration, and end-to-end levels

- Centralized logging, distributed tracing, comprehensive app monitoring

- On-call rotations with actual documented runbooks

- Proven error handling patterns

- Infrastructure management as code

- At least fifty engineers or extreme independent scaling needs.

Without these? Microservices architecture degrades delivery velocity. The development process turns chaotic without observability into how services communicate across distributed systems. Thoughtworks’ 2024 tech radar still flags “microservices envy” as a common anti-pattern.

This architecture pattern requires real investment in cloud platforms and infrastructure management. Software quality depends on DevOps maturity you may not have yet.

Event Driven Architecture

Event-driven architecture structures distributed systems around producing and consuming events. Components publish to message brokers instead of synchronous calls. Loose coupling supports resilience, independent scaling, and asynchronous communication.

This pattern shines in specific contexts. It is the standard for financial ledgers, IoT sensor networks, and high-volume e-commerce workflows. In these scenarios, the architecture’s ability to decouple producers from consumers turns fragile synchronous chains into robust, resilient streams.

With this approach, the decision is usually clearer. You either have event-centric domains or you don’t. If you’re processing streams of data that multiple consumers need, event-driven makes sense. If you’re building standard request-response CRUD apps, it likely doesn’t.

However, this decoupling introduces significant opacity. Simple debugging is replaced by the complex need to track eventual consistency and event ordering across asynchronous flows. Without advanced distributed tracing and strict schema governance, your team is effectively flying blind. This architecture demands a level of distributed systems fluency that most generalist teams simply haven’t acquired yet.

Don’t adopt this without broker expertise. If your team can’t confidently operate Kafka or RabbitMQ, start with a bounded pilot. Cloud-provider-managed services help but still require expertise. Event sourcing adds more complexity, requiring specialized knowledge.

CQRS and Event Sourcing

Command query responsibility segregation separates reads and writes into distinct data models. Event sourcing persists state changes as immutable sequences rather than current state. These design patterns often appear together in complex domains needing historical data and audit trails.

These patterns are powerful. Event sourcing delivers temporal queries, lets you rebuild read models. CQRS optimizes read and write paths independently for consistent performance. Complex domains with intricate business logic benefit from explicit state management. The architectural patterns support building robust audit capabilities and complex processing of historical data.

But I’ve seen teams add six months of complexity to projects that didn’t need it. A payments startup I advised implemented event sourcing for a system that processed a few thousand transactions a week. Completely unnecessary. They spent more time managing event schema evolution than building features.

These patterns fit:

- Regulatory environments requiring audit trails

- Financial systems needing temporal queries

- Complex processing where CRUD creates impedance mismatch

For straightforward software applications? Consider simpler design patterns. The operational overhead is significant. Event stores need different management than traditional databases. Rebuilding projections from streams demands specialized knowledge. You need distributed systems expertise you might not have.

Space-Based Architecture

I’ll keep this short because it’s rarely relevant.

Space-based architecture distributes processing and data across in-memory grids. Eliminates database bottlenecks. Linear horizontal scaling across multiple servers. Handles massive concurrent user demand.

Use cases: financial trading platforms, real-time bidding, applications with extreme traffic spikes. The space-based architecture pattern delivers consistent performance under load that would crush conventional data storage approaches.

This is rarely appropriate for your situation. Unless you’re building a trading platform or similar, skip it. Implementation details are complex. Cloud platforms can help but you need deep expertise.

Decision Framework

Here’s how to actually think about this. Your SLAs and business requirements determine how much consistency and availability your architecture needs. Match your organizational reality to pattern requirements.

| Factor | Monolith/Layered | Microservices | Event Driven | CQRS/Event Sourcing | Space Based |

| Team Size | Under 30 | 50+ | Any with streaming | DDD expertise | Specialized |

| Domain Complexity | Low-moderate | High, clear boundaries | Event-centric | Audit/temporal | Throughput-critical |

| Ops Maturity | Basic CI/CD | Full DevOps | Broker expertise | Distributed systems | In-memory grids |

| Independent Scaling | No | Per-service | Consumer scaling | Read/write split | Linear horizontal |

| Consistency | Strong | Eventual | Eventual | Event-based | Partition-based |

| Overhead | Low | High | Moderate-high | High | Very high |

CALLOUT: MYTHS TO IGNORE

- “Microservices are always better at scale” → Only with operational maturity to match

- “Monoliths can’t handle growth” → Shopify served millions on one

- “You need microservices for independent teams” → Modular boundaries work too

Are You Actually Ready?

Before adopting distributed architectures, validate these capabilities.

| Capability | Ready? | If Not… |

| One-click deploys with rollback | ☐ | Release bottlenecks |

| Centralized logging + tracing | ☐ | Incidents take hours to diagnose |

| Automated testing (all levels) | ☐ | Regressions hit production |

| Circuit breakers, retry logic | ☐ | Cascading failures |

| Documented runbooks | ☐ | Burnout, hero culture |

| Infrastructure as code | ☐ | “Works on my machine” forever |

A well-operated monolith with strong system stability beats a poorly operated distributed system. Every single time. These proven solutions matter more than architectural sophistication. DORA research consistently shows that operational maturity predicts delivery success better than architecture choice.

Growth Trajectory Matters

Your eighteen-month roadmap matters more than today.

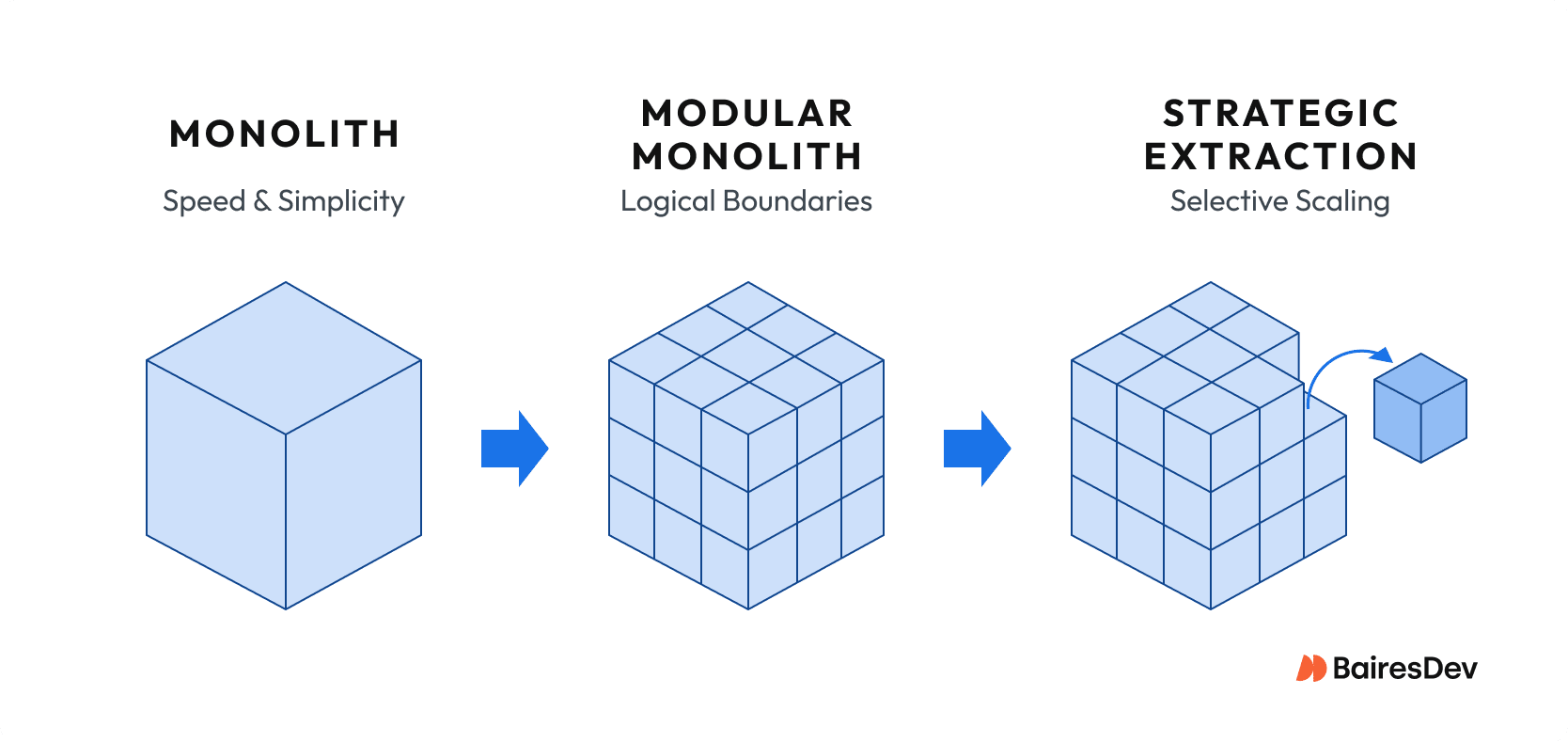

If you’re a SaaS platform expecting to triple headcount within two years: start with a modular monolith enforcing clear domain boundaries. Independent components become independent services later. Loose coupling between modules enables this evolution. The software architecture supports current needs and future scalability.

If growth is modest? Optimize for current productivity. Don’t build for scale you may never reach.

Making It Work

Architectural migration competes with features for engineering capacity. Plan sustained investment in technology and people.

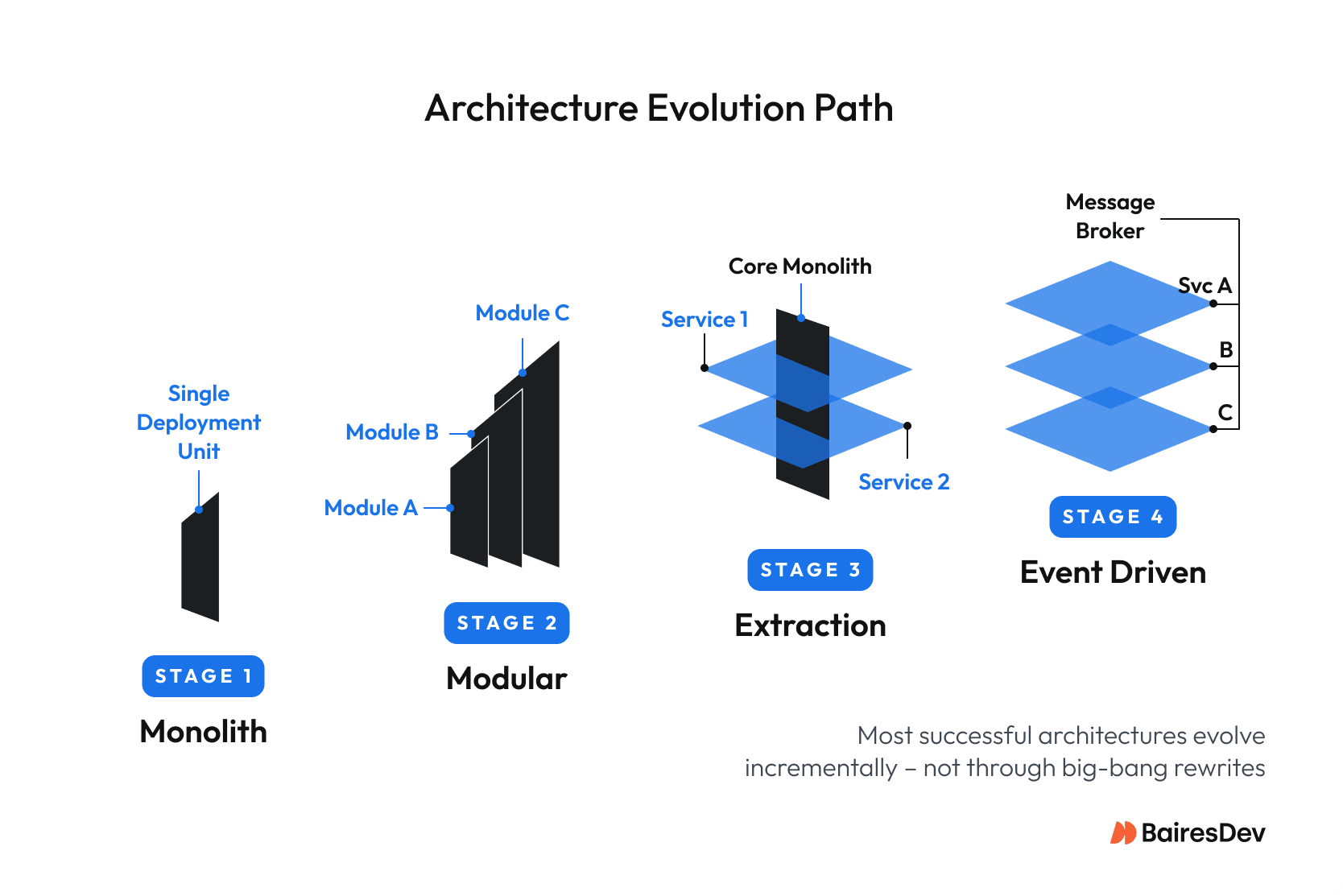

The modular monolith is gaining traction as a serious alternative to microservices. It lets teams enforce strict module boundaries within monolithic deployment. Modules communicate through defined interfaces, maintain separate data schemas, and support independent development. It provides loose coupling without the overhead of managing multiple services.

When you eventually hit the limits of a single release artifact, extract services incrementally. Target the highest-churn, most decoupled capability first. Operate that single service in production to refine your observability and release practices before splitting off anything else. Avoid the trap of a “big bang” migration.

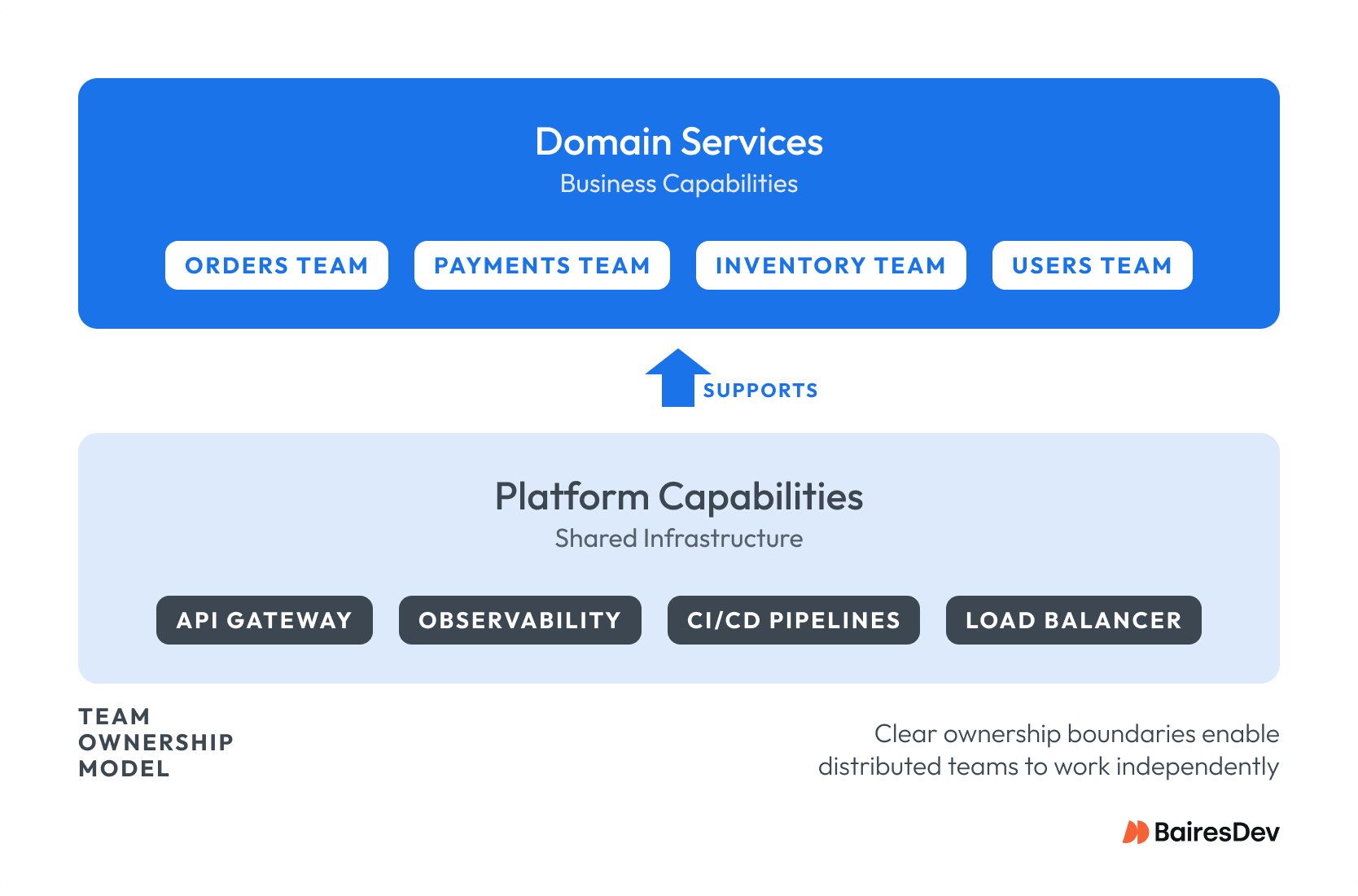

This approach is critical for distributed teams. Autonomy requires clear boundaries. Instead of treating these teams as ticket-takers, assign them ownership of complete bounded contexts or platform capabilities—like the entire API Gateway layer or the Observability stack. This structure minimizes the “coordination tax” of time zones and enables true parallel development.

Bottom Line

Architecture decisions are org decisions wearing technical clothing.

Start with the simplest architecture pattern that works. Invest in operational foundations before adding complexity. Evolve when you feel pain, not when you read a blog post covering a new trend. Finally, make sure to preserve optionality through modular design patterns.

The goal isn’t architectural elegance. It’s sustainable velocity with an acceptable operational burden and strong system stability. Building a robust, scalable architecture means matching patterns to what your organization can actually operate.