By Daniel Martins, BairesDev Senior Designer and Ludologist

When I present myself as a ludologist, many people find it peculiar and are curious to know what I actually do. In fact, my definition differs somewhat from the commonly accepted concept. For me, a ludologist is a professional who studies the ludic in its most diverse expressions—games being the most evident.

In essence, ludology is a synonym for “game studies,” which is the study of games, the act of playing them, the players, and the culture around them. The term originally emerged in the late 1990s during the International Board Game Studies Association and was coined by Gonzalo Frasca. It is an interdisciplinary activity that takes from several other areas, the most prominent being anthropology, sociology, and psychology. This cross-cultural study also aids in understanding games through history.

Obviously, the concept of ludology was born before digital games, with analog or tabletop games from the dawn of civilization. This discipline has important approaches based on social sciences, human sciences, and engineering. We should note that ludology should not be confused with gamification! While the former is a plural field of knowledge, the latter is an expression of the former. But how can we channel this into our projects? And why does it matter? I will explain.

Ludocentrism

When I was a kid, I was asked in one of my school assignments, “What do you want to be when you grow up?” Without blinking, I replied that I wanted to be exactly what I am today: “an Engineer of Things.” I did not major in that, since that degree does not even properly exist. I graduated with a degree in industrial design, but I feel like I am an Engineer of Things because, throughout my almost 20 years of career, I have been adding knowledge, methods, techniques, approaches, and tools that allow me, nowadays, to develop any type of project. In other words, build anything. Therefore, an actual Engineer of Things.

The beauty behind children’s reasoning is the ability to imagine something seemingly impossible, nonexistent, and even “absurd.” That same creativity and fertile imagination are things that accompany me to this day because I never lost my proximity to games and I always found a way to enjoy and have fun in the simplest things. This allows me to enjoy ludic behavior, or as I usually call it, ludocentrism. And before you think that this is something exclusive to Engineers of Things like me, think twice. Playful behavior is something inherent in human beings and even animals. Johan Huizinga, the Dutch historian and linguist, wrote in his book Homo Ludens (1938) that animals, such as puppies, “invite one another to play by a certain ceremoniousness of attitude and gesture. They keep to the rule that you shall not bite, or not bite hard, your brother’s ear. They pretend to get terribly angry. And—what is most important—in all these doings they plainly experience tremendous fun and enjoyment.” They play without even having a language!

Still, according to Huizinga, even in its simplest forms, a game (understood as behavior) is more than just a physiological phenomenon or a psychological reflex. It goes beyond the limits of purely physical or biological activity. It is because of this very ludocentric behavior that I look to other theories and knowledge in order to better understand what ludicity and games can convey. One of the concepts I find most fascinating is that of flow. Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, a psychologist of Croatian origin, came up with the concept of flow as a highly focused mental state. Have you ever stayed up all night playing games, whether it is the new video game you just bought or your favorite board game, without feeling hungry or tired, and without realizing it, a new day has dawned? If the answer is yes, congratulations. You have experienced a flow state.

Games, as meaningful experiences as they are, allow us to experience a state of complete involvement in what is happening, with extreme focus and absolute concentration. They provide clarity of what must be achieved and inform us how well we are doing, without leaving out the excitement. We know how good we perform and how adequate our skills are because we have immediate feedback in a game. All this is a consequence of intrinsic motivation—the reward is whatever element produces the flow.

This is where gamification comes in.

What is NOT gamification?

Since its emergence in the early 2000s, gamification has been gaining a lot of attention in several industries—from education to technology companies—and is increasingly present in our lives without us even realizing it (I’m looking at you, social media companies). Due to its current popularity, it is common to see misconceptions and dubious applications of the term, which often do not contribute to expanding its use. Before explaining what gamification is, let’s understand what it is not:

- It’s not about using games … but it could be — Simply using a video game or board game during a training or some other experience does not mean that this context has actually been gamified. However, these “tools” can be part of a gamified experience.

- Giving points for no reason — It is very common to see gamified solutions that have point programs, like airline miles programs. Yet it does not always connect with the real needs of users (hereafter called players), not to mention the unrealistic amount of points needed to obtain rewards.

- Using game terms — Things like “level up,” “experience points,” and “difficulty levels” often only promote an aesthetic layer of gamification, which is incipient and insufficient to achieve the real objectives and potential benefits of the method.

- It’s not always digital — Gamification is not exclusive to digital solutions. As stated above, it is a method and can be applied in any situation, including people’s daily lives, without dependence on technology.

- Solution for all problems — As a method, specifically a design method, it should be human-centered. Each individual is a complex universe, with needs, visions and values different from the others. It is, at the very least, presumptuous and even dishonest to say that gamification will be responsible for the success of an endeavor or will solve all the problems in a given situation.

More and more often, people demand personalization and exclusivity, and one solution will not always meet everyone’s expectations or meet their playful needs. Don’t know what it is? I will explain.

What gamification actually is

Gabe Zichermann and Christopher Cunningham define in their book, Gamification by Design: Implementing Game Mechanics in Web and Mobile Apps, that gamification is “the process of game-thinking and game mechanics to engage users and solve problems.” For me, it is a method that uses elements normally found in games and game design techniques, applied in non-playful contexts, to engage players, promote behaviors and facilitate the acquisition of new knowledge.

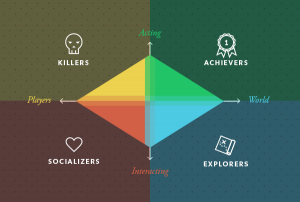

Although it seems easy, it is mandatory to understand the players’ real playful needs. To better understand what this means, let us once again quote great minds to broaden our vision. Bartle’s taxonomy of player types is a classification of video game players developed by Richard Bartle, a British writer, professor and game researcher. According to Bartle there are four types of video game players:

Source: Evato Tuts+

- Achievers — Players who prefer to gain “points,” levels, equipment and other concrete indicators of succeeding in a game.

- Explorers — Players who prefer discovering areas and immersing themselves in the game world and narrative.

- Socializers — Players who gain the most enjoyment from a game by interacting with other players and, sometimes, computer-controlled characters with personalities.

- Killers — Players motivated by power gaming and eclipsing others. They like to win and defeat others.

Note that while the first two types prefer to interact with the game, the last two achieve satisfaction through interaction with other players. The relevance of these psychological aspects helps us select the ideal actions or techniques to engage them in the process of developing a game or ludic experience. Through this, we meet these ludic needs and promote the right type of entertainment for players. In other words: the psychology behind gamification helps us make better project decisions.

Over the last 10 years as a ludologist, I have often heard people say that they don’t have the habit of playing or that they don’t have fun playing games. That is probably because they have not found a game that delivers the kind of fun that satisfies their playful needs. Nicole Lazzaro, Founder and President of XEODesign, Inc., introduced the Four Keys, a proven practical model that helps companies craft emotions to create deeper engagement with gamification:

- Easy Fun — This is about finding novelty, and is driven by curiosity from exploration, role-play, and creativity.

- Hard Fun — The fun of challenges. One particular emotion associated with this is “fiero,” a type of pride felt after conquering a challenge.

- People Fun — Amusement is obtained from competition and cooperation, as a consequence of friendship and human relations.

- Serious Fun — Excitement from watching the player and their world change through the pursuit of meaning.

Different players will consciously or subconsciously seek to meet their playful needs, and understanding these psychological and emotional aspects helps us design more meaningful experiences, whether they are gamified or not, whether you are a designer or a software developer. In its almost 20 years of existence, the gamification market has been flooded by a series of frameworks, and one of them, which I adopted as my main one and which connects all these aspects mentioned above, is Octalysis by Yu-Kai Chow.

Octalysis differs from other frameworks precisely because it states that human beings are motivated by different Core Drives, which in my opinion are precisely those ludic needs that we all share, to a greater or lesser extent. These needs are reflected in the search for an “Epic Meaning,” the relationships we develop through “Social Influence” and even the engaging fear of the Core Drive “Loss and Avoidance.” Yes, even negative feelings like fear can be used to create meaningful experiences as long as it’s in a moderate, ethical and responsible way.

Practical examples

We can apply ludocentrism as a lens that allows us to see reality in a different way or even redesign our social or relationship structures. When we compare, for example, games with work we find clear differences:

Games

- Repetitive but fun tasks

- Provides us with constant feedback

- Contains a volume of information adequate to the needs of the moment

Work

- Repetitive tasks but usually boring

- No profound feedback. Generally, performance evaluations do not always take into account transformations, personal evolution, or momentary difficulties.

- We are given too much information and still not enough for our demands.

In games, we perceive our personal evolution in a clear and tangible way, as opposed to the obscure way it happens at work. These things are a consequence of something else that games offer us that companies do not always give us: autonomy. Playing a game is a voluntary choice, in which the system offers you all the necessary tools to get through. And even though it is not one of the conceptual goals perceived by many game theorists and scholars, games invariably provide us with fun.

Working with agility and agile software development methods can be complex or complicated, even more so for someone who is starting out and needs to understand all their roles and rituals. I had the opportunity to participate in a ludocentric exercise called Fun Retrospectives. This dynamic was inspired by a book of the same name, written by Paulo Caroli and Tainã Caetano Coimbra, with activities and ideas for making agile retrospectives more engaging. During retrospective meetings, we used themes such as Pokémon and Star Wars, reflecting and responding about our individual practices and as a team, in a light, fun, and much more engaging way.

That’s not all. Ludocentrism helped me in my daily life, enabling this light and fun posture that increased my performance and that of my colleagues. When we are having fun, especially when playing games, our brain works more efficiently in addition to the state of flow that naturally increases our performance, and it all ultimately makes us happier. Do you know why? When we play, our brain produces a series of beneficial neurochemicals, such as serotonin, which inspires a feeling of serenity and increases our hope. Low levels of this substance are associated with the manifestation of depression. Another neurotransmitter we produce is dopamine, responsible for relaxation, euphoria, and pleasure. When we have low levels of dopamine, we feel stressed or even feel pain more acutely.

Why does it matter?

As if all the benefits mentioned above were not enough, not only implementing gamification but also practicing ludocentrism in our projects and in our daily lives helps us develop our creativity, a skill that has become important in recent years. It is now mentioned in several current studies on the future of work as a fundamental competence and a great competitive differential.

As a creative child (which for me is redundant, as children are naturally creative beings), I was able to envision a field that did not exist. But when I consider that in Brazil the field of UX Design started gaining traction just over a decade ago and that so many other fields were non-existent until recently (content creation, eSportist), I see the relevance that playfulness holds in our lives.

Another profession with a singular name that I acquired in a self-taught way was that of a Futurist, a professional who embraces uncertainty as a resource to create possibilities and plural visions of the future. One of the largest research centers in future studies, the Institute for the Future, says that in 2030, about 85% of the professions that will exist have not been invented yet. How awesome is that?

I leave here an open invitation for everyone: think and create these futures together! I guarantee one thing. It will be a lot of fun!

More blog posts from our BDevers.